Hemorrhagic strokes

Hemorrhagic stroke (CMP) is characterized by intracranial haemorrhage into the cerebral parenchyma (intraparenchymatous haemorrhage) or into the ventricular system (subarachnoid haemorrhage). Hemorrhagic CMP accounts for approximately 20% of all strokes. [1] They are associated with lower survival than ischemic strokes, 2/3 of patients die within half a year of stroke.[2]

Bleeding into the brain parenchyma[edit | edit source]

__ Krvácení do mozkového parenchymu

Abstract[edit | edit source]

Bleeding into the cerebral parenchyma (intraparenchymatous hemorrhage, hereinafter IPH ) is characterized by a sudden focal deficit that worsens within seconds to minutes , often associated with cephalalgia , nausea , vomiting and coma . Etiologically , hypertension , vascular malformations , vasculopathy , coagulopathy , etc. are involved. IPH reliably demonstrates CT or MRI . Treatment and prevention of recurrence depends on the etiology .[1]

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

IPH accounts for approximately 10-15% of strokes , with a worldwide incidence of 10-20 cases per 100,000 people . The incidence is higher in men, in older age, and in the black and Asian populations . Other risk factors include hypertension , smoking , alcoholism (-> cirrhosis , thrombocytopenia ) or low serum cholesterol (eg after intensive statin therapy ). Among genetic risk factors, the presence of alleles for apolipoprotein E ε2 and ε4 is used, which are involved in the deposition of amyloid in cerebral vessels, amyloid angiopathy. ref name="Brust"/>

Patogenesis[edit | edit source]

In hypertensive patients , bleeding occurs at the bifurcation sites of the small penetrating arteries, which are scarred due to hypertension and have degenerated media. Another separate cause of IPH is the presence of pathologically altered, fragile vessels due to cerebral amyloid angiopathy . Other reasons are:

- vascular malformations ( AV malformations , AV fistulas and cavernous angiomas);[1]

- hemorrhagic diathesis ( hemophilia , thrombocytopenia , leukemia , liver disease);[3]

- anticoagulant therapy - long-term warfarinization is the cause of IPH in up to 10% of patients, especially when combined with other risk factors;

- cerebrovenous occlusion in sagittal sinus thrombosis, a rare diagnosis to be considered in increased risk of thrombus formation;

- hyperperfusion syndrome in patients who have undergone revascularization by carotid endarterectomy , in which cerebral perfusion suddenly increases and leads subjectively to headaches, confusion, focal deficits and even IPH;

- substance abuse - sympathomimetics such as amphetamine , methamphetamine and cocaine ;

- tumors that can also bleed, for example in high-grade glioblastoma ;[1]

- hemorrhagic transformation of ischemic stroke , where reperfusion damage of ischemically altered tissue is involved in pathogenesis.[4]

The bleeding itself stops spontaneously shortly after the onset of the stroke, bleeding lasting for several hours is less common (usually in uncorrected coagulopathies). Extravascular blood (hematoma) contains proteins that act osmotically in the brain and is involved in the formation of edema , which oppresses its surroundings. It is not clear whether ischemia develops in the surrounding parenchyma, but rather suppression of brain tissue activity (diaschisis). This hypothesis is confirmed by the fact that the correction of hypertension after IPH is safe. [1]

Clinical picture[edit | edit source]

Patients with IPH develop focal neurological deficits , such as contralateral hemiparesis, loss of sensation, quadriplegia, etc. (depending on the location of the lesion). The deficit worsens within minutes and is often associated with acute hypertension ( Cushing's reflex ). Cephalgia occurs in less than 50% of cases. Increased intracranial pressure due to hematoma leads to nausea , vomiting and alteration of consciousness .[1]

It should be noted that the clinical picture cannot distinguish between hemorrhagic and ischemic stroke .[1]

Diagnostics[edit | edit source]

The key to the detection of IPH is the CT of the head, which is usually the method of choice for the speed of examination.[1] Hemorrhage appears to be a hyperdense lesion on CT. [3] An alternative is MRI , which is more sensitive than CT for some aspects of IPH, eg for vascular malformations or brain tumors on contrast MR examination with gadolinium.[1]

Other important examinations include:

- bleeding tests ( APTT , PT , platelet function);

- blood count ;

- liver function tests ;

- ECG ;

- x-ray s + p;

- in selected patients urinary toxicology . [1]

In patients less than 50 years of age with an unexplained source of bleeding, angiography should be performed to rule out vascular anomalies, or in case of infarction in the area of venous canals venography to exclude venous thrombosis.[1]

Terapeutic procedure[edit | edit source]

The aim of treatment is to minimize brain damage and prevent systemic complications :

First contact[edit | edit source]

Provide first aid according to ABC rules (Airway, Breath, Circulation), intubation in patients with impaired consciousness, bulbar dysfunction or respiratory insufficiency. Look for signs of trauma . If we find an unconscious patient, we treat him as if he had a spinal injury until proven otherwise. After placing on the bed, the head of the bed should be inclined at 30 ° for optimal pressure and perfusion of the brain. If rehydration is necessary, we use physiological solution (we avoid hypotonic solutions and lactated ringer!). The patient should be admitted to the intensive care unit as a matter of urgency. [1]

Stop bleeding[edit | edit source]

In 40% of patients, the hematoma expands within 24 hours, which is the most common cause of neurological deterioration. The goal is to lower blood pressure below 160/90 mmHg . It is also given in labetalol or nicardipine . In hypertensive crisis , sodium nitroprusside is being considered, but its vasodilating effect increases intracranial pressure.[1]

In warfarin-induced IPH , an attempt is made to correct artificial coagulopathy. In practice, activated factor VII or prothrombin complex concentrate is used .[1]

Surgical treatment of hematoma evacuation is used only in patients with cerebral hemorrhage , where there is a risk of strain oppression, in patients with vascular malformations (and a good prognosis) and in young people with moderate to major bleeding who worsen clinically . In contrast, surgery is contraindicated in minor bleeding with a small neurological deficit and in patients with GCS below 5 , except for the aforementioned cases of cerebral hemorrhage.[1]

Prevention of secondary damage[edit | edit source]

Hematoma and subsequently edema increase intracranial pressure (ICP) and contribute to the oppression of surrounding structures, herniation and deterioration of the clinical picture. To monitor intracranial pressure, an ICP monitor or similar CT scan twice daily for the first 48 hours can be used to monitor hematoma progression. Antiedematous therapy should only be used in case of neurological clinical deterioration or evidence of herniation on CT and not prophylactically. Mannitol 0.25–1.0 g / kg is administered in boluses up to a target plasma osmolality of 320 mOsm / l . Hyperventilation lowers ICP, but this is only a temporary solution. Both mannitol and hyperventilation should be discontinued gradually , otherwise a rebound phenomenon will occurand the rise of ICP.[1]

During acute IPH , a seizure may occur which may worsen ICP -> anticonvulsants . Corticosteroids are not important in acute IPH.[1]

Prevention of recurrence[edit | edit source]

The combination of thiazide diuretics and ACE inhibitors in the control of hypertension halved the recurrence rate. Patients with amyloid angiopathy should avoid antiplatelet therapy, including aspirin.[1]

Systemic complications[edit | edit source]

They are the same as in all unstable, immobile patients. Complication:

- Cardiovascular : IPH often accompanies ECG changes and subendocardial ischemia. Antiplatelet therapy should be discontinued to prevent coronary ischemia for several weeks;

- pulmonary : represents aspiration of gastric contents and pulmonary embolism in immobilized. Compression stockings are used to prevent embolism and three days after bleeding in stable patient doses of heparin or heparinoids;

- infectious : pulmonary, urinary, cutaneous, venous;

- metabolic : hyponatremia due to SIADH , isotonic crystalloid therapy;

- mechanical : prevention of pressure ulcers in immobilized.[1]

Rehabilitation after a hemorrhagic stroke, as with an ischemic stroke, should begin as soon as possible.[3]

Links[edit | edit source]

Related articles[edit | edit source]

- Hemorrhagic strokes

- Subarachnoid hemorrhage

- Ischemic stroke

- Stroke / PGS

- Hemorrhagic stroke / PGS / diagnostics

- Ischemic stroke / PGS / diagnostics

External links[edit | edit source]

Literature[edit | edit source]

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s BRUST, John C. M. Current diagnosis and treatment, Neurology. 2. edition. Singapore : McGraw-Hill, 2012. ISBN 9780071326957.

- ↑ AMBLER, Zdeněk – BEDNAŘÍK, Josef, et al. Klinická neurologie : část speciální. II. 1. edition. Praha : Triton, 2010. ISBN 9788073873899.

- ↑ a b c BEDNAŘÍK, Josef – AMBLER, Zdeněk, et al. Klinická neurologie. Část speciální II. 1. edition. Praha : Triton, 2010. ISBN 9788073873899.

- ↑ LIEBESKIND, Davis S. - [online]. The last revision 8.3.2013, [cit. 2013-03-22]. <https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1916662-overview>.

Bleeding into the subarachnoid space[edit | edit source]

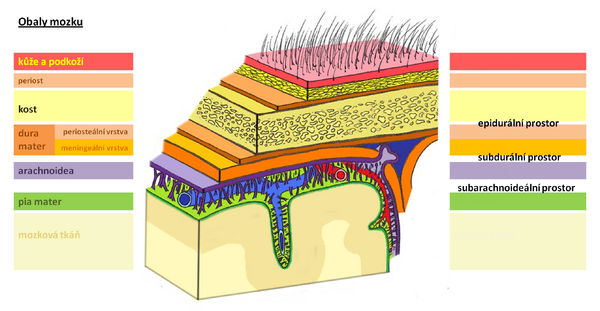

In subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAK), blood leaks into the cerebrospinal fluid between the arachnoid and the pia mater . This is a massive bleeding from an arterial basin.

Causes[edit | edit source]

It most often occurs during rupture of the aneurysm (60%), in the area of the Willis circuit , especially on the a. Communicans anterior or posterior, often during an increase in blood pressure (physical exertion, coitus, agitation, defecation, etc.). Other causes may be trauma, vascular malformations such as arteriovenous and cavernous malformations , anticoagulant therapy , bleeding disorders , hypertension , amyloid angiopathy , primary vasculopathy. Idiopathic (cryptogenic) SAKs also occur. Traumatic SAKs are then often associated with contusion .

Clinical picture[edit | edit source]

The headache appears within seconds and can be very intense. It is located on both sides, sometimes with a maximum occipital. Initially, there may be a brief disturbance of consciousness . The pain is further accompanied by nausea , vomiting , photophobia and phonophobia . Meningeal syndrome develops within minutes to hours . Patients are often disoriented, confused, some patients are somnolent only in dimention , sometimes psychomotor restlessness, aggression, negativism can sometimes dominate . During the promotion of SAK intracerebrally, focal symptoms develop. The patient's condition is assessed on a Hunt and Hesse scale - see vascular disease of the brain .

![]()

Diagnostics[edit | edit source]

The diagnosis is determined by CT examination. About 5% of CT scans in the first 24 hours do not show SAK, so if the suspension lasts for SAK, we indicate cerebrospinal fluid examination. A typical cerebrospinal fluid finding is oxyhemoglobin in spectrophotometric examination .

Therapy[edit | edit source]

If SAK is demonstrated, we refer the patient for neurosurgery for brain panangiography, which should be performed within 72 hours of the onset of the problem due to the risk of vasospasm. If an aneurysm is found and if the score according to H + H is up to 3, an operation is indicated - either clipping the neck of the aneurysm or filling the cavity of the aneurysm with a detachable spiral - coiling . Bed rest ( always hospitalization ), symptomatic treatment ( analgesics , antiemetics , correction of hypertension ) are essential. Vasospasm can be suppressed by calcium ion blockers .

If the aneurysm is not detected, the patient is treated conservatively - opiates for pain, administration of mucolytics and laxatives, and after 3-6 weeks, control panangiography is indicated.

Bleeding from an aneurysm[edit | edit source]

An aneurysm is a limited extension of the cerebral artery. The bulge is caused by the long-term effect of blood pressure on the weakened blood vessel wall (congenital defects, atherosclerosis , fungal infections, trauma, etc.). The arches thin the vascular wall, which ruptures when the blood pressure suddenly increases (exertion, defecation, coitus, anger, forward bend). Aneurysms are most often found in the area of the Willis circuit , especially on the internal carotid artery , a. Communicans ant., A. Cerebri media ).

Bleeding from a cerebral aneurysm is relatively common in the Czech Republic (about 600 cases of SAK per year), unfortunately with a very high lethality (40% of patients die after the first bleeding). The aneurysms themselves (especially of smaller size) are clinically silent until rupture and bleeding occur.

Clinical picture[edit | edit source]

The manifestations are sudden, dramatic and rapidly progressing. The initial symptom is intense headache (severe, as yet unknown) , nausea , vomiting , increase in systemic pressure due to Cushing's reflex, photophobia, impaired consciousness , focal neurological findings according to the location of the aneurysm, epileptic seizures , meningism , fever may be present, cranial nerve lesions ( III and VI ) etc.

Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

To determine the diagnosis of SAK, it is necessary to perform a CT examination (detection of blood in the cerebrospinal fluid, intracerebral hematoma), which may even roughly outline the source of bleeding. He then specifies the brain panangiography , which we try to perform, as soon as possible after the diagnosis of SAK, and always in at least two projections. In patients without intracranial hypertension, in whom CT was not sufficiently conclusive, we perform CSF sampling and examination (evidence of the presence of erythrocytes or xanthochromin).

The therapeutic procedure is based on the Hunt and Hesse classification .

- grade 0 - non-bleeding aneurysm, without symptoms,

- grade I - headache, neck opposition , mild meningeal syndrome,

- grade II - headache, neck opposition, cranial nerve lesions , more pronounced meningeal syndrome,

- grade III - attenuation or confusion, mild focal finding,

- grade IV - stupor , decerebratory rigidity , vegetative disorders ,

- grade V - deep coma , decerebratory rigidity.

Therapy[edit | edit source]

Arteriovenous malformations[edit | edit source]

Iron

AV malformation (AVM) is an innate envelope of arteries and veins that communicate directly with each other and between which a capillary system has not been formed. Due to the defect, the resistance of the capillaries is negligible, which results in an increase in blood flow in malformed vessels. At the expense, other areas are less perfused and subject to ischemia ( steal phenomenon ).

Clinically, it is manifested by bleeding (70%), not only SAK, but also intracerebral. Ischemia of less perfused parts leads to focal manifestations according to location (eg epileptic seizures).

For basic diagnostics we use CT and MRI , the source of bleeding is then clarified using PAG.

Therapy[edit | edit source]

Malformations are extensive and often difficult to access surgically. If these are not very acute cases, we choose the "watch and scan" method , in which we evaluate the condition of individual vessels and their progression over time. Subsequently, we perform surgery on arteries that could be risky.

The operation consists in closing the supply arteries by bipolar coagulation (performance is many hours and difficult). An alternative is to embolize the arteries endovascularly, or to use a Leksell gamma knife .

Cavernous hemangioma[edit | edit source]

Iron

This is a special type of AVM. The cavernoma is a limited, small vascular formation in the brain tissue that does not have wide supply arteries. For this reason, it is not clearly visible on PAG, so we prefer MRI for diagnosis.

Bleeding is not extensive, but relatively common.

Differential diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Links[edit | edit source]

Related articles[edit | edit source]

- Treatment of intracranial aneurysm

- Article for graduate students

- Craniocerebral trauma

- Brain vessels

- Stroke

- circle of Willis

- Aneurysm

- Arteriovenous malformations

- Cavernous malformations

Reference[edit | edit source]

- NEVŠÍMALOVÁ, Soňa – RŮŽIČKA, Evžen – TICHÝ, Jiří. Neurologie. 1. edition. Praha : Galén, 2005. pp. 163-170. ISBN 80-7262-160-2.

- AMBLER, Zdeněk. Základy neurologie. 6. edition. Praha : Galén, 2006. pp. 171-181. ISBN 80-7262-433-4.

- ZEMAN, Miroslav, et al. Speciální chirurgie. 2. edition. Praha : Galén, 2004. 575 pp. ISBN 80-7262-260-9.

Source[edit | edit source]

- BENEŠ, Jiří. Studijní materiály [online]. ©2007. [cit. 2009]. <http://www.jirben.wz.cz/>.