Heart failure (internal)

Heart failure is a condition where the heart is unable to pump blood in accordance with the body's metabolic needs.

Chronic heart failure is a condition affecting the heart in which, despite sufficient filling of the ventricles, the minute output decreases and the heart is unable to cover the metabolic needs of the tissues (delivery of oxygen and nutrients and removal of carbon dioxide and metabolic waste products). Heart failure without a decrease in cardiac output can occur with an unreasonable rise in ventricular filling pressure.

Chronic heart failure is a condition affecting the heart in which, despite sufficient filling of the ventricles, the minute output decreases and the heart is unable to cover the metabolic needs of the tissues (delivery of oxygen and nutrients and removal of carbon dioxide and metabolic waste products). Heart failure without a decrease in cardiac output can occur with an unreasonable rise in ventricular filling pressure [1].

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

Both the incidence and the prevalence of chronic heart failure are increasing in developed countries, which is caused both by the aging of the population and also by the improving treatment of acute coronary events (patients have damaged myocardium after ACS).[2]

- Incidence 1-2%.

- The average survival time from diagnosis is 3.2 years for men, 5.4 years for women.

Distribution[edit | edit source]

- according to the rate of formation

- Acute

- Chronic

- according to localization (right-sided, left-sided, bilateral)

- by dysfunction (systolic, diastolic)

Current guidelines classify heart failure according to left ventricular ejection fraction into:

- HFrEF (heart failure with reduced ejection fraction) - EF LV <= 40%,

- HFpEF (heart failure with preserved ejection fraction) EF LV >= 50%,

- HFmrEF (heart failure with mid-range ejection fraction) EF LV = 40-49%. [3]

Left ventricular diastolic dysfunction is thought to be the underlying abnormality in patients with HFpEF and possibly also HFmrEF. [3]

- Congestive heart failure - signs of heart insufficiency appear along with symptoms of venous congestion (in the pulmonary or systemic basin). It is not synonymous with right-sided heart failure or heart failure with peripheral edema.

- Compensated heart failure - symptoms of heart failure have disappeared due to compensatory mechanisms or due to treatment.

Etiology[edit | edit source]

The most common cause of heart failure is CHD (about 70%), untreated or poorly treated hypertension and cardiomyopathy (about 20-30%). The most common cause of acute right-sided heart failure is pulmonary embolism. Right-sided chronic heart failure is most often caused by left-sided heart failure. [2]

- Left-sided failure :

- contractility disorders ( IHD, KMP, myocarditis, amyloidosis, sarcoidosis ),

- excessive volume load – ↑ preload ( chronic renal failure, aortic and mitral insufficiency, shunt defects),

- excessive pressure load – ↑ afterload ( aortic stenosis, obstructive cardiomyopathy, arterial hypertension ),

- LV filling disorder (constrictive pericarditis, mitral stenosis ),

- high demands on the body – anemia, thyrotoxicosis, pregnancy,

- substance and drug effects – alcohol, antiarrhythmics.

- Right side failure :

- contractility disorder (IHD, KMP, myocarditis,...),

- excessive volume load ( pulmonary insufficiency or tricuspid insufficiency ),

- excessive pressure load ( pulmonary embolism, pulmonary hypertension, cor pulmonale in COPD or pulmonary fibrosis ),

- RV filling disorder ( cardiac tamponade, tension pneumothorax, constrictive pericarditis, tricuspid stenosis ).

- Bilateral failure :

- failure of both chambers due to a process that affects both (IHD, KMP, constrictive pericarditis),

- primary LV failure – congestion in the lungs → vasoconstriction of arterioles (protection against pulmonary edema ) → development of pulmonary hypertension → secondary PK failure.

Compensation mechanisms[edit | edit source]

- Activation of the sympatho-adrenal system (↑ TF, vasoconstriction, ↑ myocardial contractility).

- Activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone axis (Na + and water retention, vasoconstriction, ↑ myocardial contractility ).

- Myocardial hypertrophy.

- Redistribution of cardiac output to vital organs.

- Utilization of anaerobic metabolism.

Compensatory mechanisms ensure short-term compensation, but in the long-term they have an adverse effect (↑ cardiac work, ↓ myocardial perfusion, fluid retention with swelling, K+ losses and arrhythmias.

Consequences of heart failure[edit | edit source]

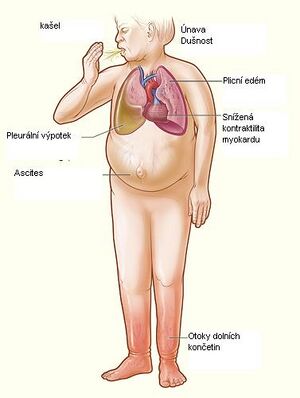

Manifestations of heart failure Failure of the pumping function of the heart leads to:

- Impaired supply of target organs with oxygen,

- kidneys (retention of water and Na + ) – swelling,

- CNS – intellectual disorders,

- muscle - fatigue,

- liver – reduction of proteosynthesis(hypoalbuminotic edema, bleeding ) and detoxification ( accumulation of ammonia and other toxins ).

- Occupancy in the systemic and pulmonary basins,

- shortness of breath to orthopnea, pulmonary edema, increased pulmonary resistance ( pulmonary hypertension ),

- edema, ascites, hydrothorax,

- hepatomegaly,

- heart rhythm disorders – atrial fibrillation (due to atrial dilation), embolization, gallop, tachycardia.

- Activation of cardiomyocyte apoptosis and fibroproduction,

- loss of cardiomyocytes and replacement with tissue (LV remodeling) – ventricular compliance decreases,

- decrease in Ca2+ – arrhythmia.

Clinical signs [2][edit | edit source]

Skiagram of the chest in congestive heart failure Increased filling of jugular veins

Symptoms of congestion in the pulmonary basin - left-sided heart failure[edit | edit source]

As a result of congestion in the pulmonary venous bed, interstitial pulmonary edema occurs, later alveolar edema. In the most severe cases, cardiogenic shock may develop.

- Dyspnea : exertional dyspnea is typical, in the most severe phase paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea ( asthma cardiale ). Relief is brought by sitting down ( ortopnoea ), so the patient adds pillows under his head and essentially sleeps in a semi-sitting position.

- Tachypnea is a manifestation of interstitial pulmonary edema.

- Foamy sputum : rarely it can be pinkish ( sputum croceum )

- Central cyanosis with a decrease in Hb oxygen saturation occurs in more severe cases.

- Crackles can be detected by auscultation over the bases of the lungs or diffusely.

Symptoms of congestion in the systemic circulation - right-sided heart failure[ edit source ][edit | edit source]

- Increased filling of jugular veins, event. systolic pulsations of the jugular veins

- Hepatojugular reflux

- Hepatomegaly

- Swelling of the lower limbs

- Pleural effusion, event. shortness of breath as a manifestation of effusions

- Ascites

- Dyspepsia to malabsorption (congestion of splanchnic veins)

Symptoms with reduced ↓ MSV[edit | edit source]

- Fatigue, muscle weakness, pain

- Systemic hypotension to cardiogenic shock - fatigue, bradypsychia, pallor, cool periphery, impaired consciousness

- Tachycardia, gallop rhythm (3rd sound)

- Pulsus alternans in severe heart failure

- Metabolic acidosis

- Oliguria, sodium retention, nocturia (from decreased renal perfusion)

- Disorder of proteosynthesis ( albumin, coagulation factors ), detoxification ( subicterus), cachexia (from decreased liver perfusion)

Diagnostics[edit | edit source]

- Anamnesis ;

- Physical examination ;

- Electrocardiographic examination (to determine the etiology);

- Laboratory examination:

- BNP/NT-proBNP – normal values in untreated patients rule out the diagnosis for 90%,

- blood count – in advanced failures there is often normocytic, normochromic anemia,

- liver tests,

- renal function tests (creatinine, urea), mineralogram - monitoring of values due to pharmacological therapy;

- Imaging examination:

- chest skiagram:

- pulmonary congestion (increased vascular pattern),

- butterfly wings – the effusion is in the interstitium, on the x-ray there is a shadow in the central fields,

- Kerley's line – thickening of the interlobar septa,

- assessment of the cardiothoracic index (KTI) – the ratio of the maximum width of the heart shadow to the maximum width of the internal chest – pathological is a KTI > 0.5,

- a negative result does not rule out heart failure.

- echocardiography – basic method:

- assessment of systolic function according to ejection fraction (EF>50% is normal, EF 40–50% is mild dysfunction, 30–40% is moderate dysfunction, <30% is severe dysfunction),

- assessment of diastolic function,

- accurately only invasively,

- in practice, it is measured by Doppler examination of the mitral flow (transmitral Doppler curve), the size of the left ventricle and the speed of movement of the mitral annulus are assessed,

- isotopic ventriculography is an accurate method to determine the ejection fraction;

- chest skiagram:

NYHA classification of dyspnea[edit | edit source]

The NYHA ( New York Heart Association ) classification of dyspnea is currently the most widely used. It is primarily intended for the classification of dyspnea in heart failure, but is also commonly used to assess dyspnea of other etiologies.

| NYHA dyspnoea classification [4] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Class definition | Limitation of activity | |

| NYHA I | It can't handle only higher effort, faster running. | It is not limited in everyday life. |

| NYHA II | He can walk as fast as possible, but not run. | Fewer restrictions in everyday life. |

| NYHA III | Only basic household activities, walking 4 km/h. Normal activity is already exhausting. | Significant limitation of activity at home. |

| NYHA IV | Shortness of breath with minimal exertion and at rest. Necessary help from another person. | Fundamental limitations in life. |

Differential diagnosis[edit | edit source]

- Left heart failure - distinguish between cardiac and bronchopulmonary dyspnea

- lungs (acute respiratory attacks) – cough is chronic, expectoration of purulent sputum, expiratory rales, wheezing

- heart (acute pulmonary edema) – shortness of breath is provoked by a horizontal position, sputum foamy, pinkish

- Right heart failure

- peripheral edema

- symmetrical - in renal disease, nephrotic syndrome, hypoalbuminemia, in liver disease, malabsorption syndrome

- asymmetric – deep vein thrombosis, chronic venous insufficiency

- hepatomegaly – in right heart failure there is always ↑ filling of the jugular veins

- peripheral edema

Causes of death in heart failure[edit | edit source]

- Arrhythmia ( ventricular fibrillation ).

- Pulmonary edema (failure of ventilation).

- Thromboembolism (to the lung from DK deep vein thrombosis ).

- CHD.

Treatment of acute heart failure[edit | edit source]

Acute left-sided failure [2][3][edit | edit source]

- Treatment of pulmonary edema and asthma cardiale :

- positioning (sitting or semi-sitting),

- efforts to ↓ venous return ( ligature of 2–3 limbs for 10–15 min with rotation),

- inhalation of oxygen by mask (if saturation does not rise to at least 85%, PEEP or UPV is used),

- antitussives - codeine ( morphine and its analogues) or non-codeine

- administration of loop diuretics (furosemide 40-125 mg IV) and infusion with potassium (furosemide leads to its depletion).

- In heart failure with low MSV and hypotension (< 90 mmHg), it is appropriate to consider:

- catecholamines – dobutamine, dopamine,

- phosphodiesterase inhibitors ( positive inotropic and vasodilating effect ) – milrinone,

- calcium sensitizers – levosimendan ( positively inotropic without increasing oxygen and energy requirements ).

- In heart failure with hypertension (> 90 mmHg), it is appropriate to consider:

- vasodilatation – nitroglycerin, isosorbide dinitrate, nitroprusside, nesiriside.

- For atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response, digoxin 0.25 mg iv and/or β-blockers. Amiodarone may be considered.

- Device treatment comes when the previous treatment is insufficiently effective. In case of insufficient diuresis, a continuous elimination method is indicated (continuous veno-venous hemofiltration or slow continuous ultrafiltration). Cardiac stimulation is indicated in case of bradyarrhythmia. Intra-aortic balloon counterpulsation can be used especially in cardiogenic shock as a temporary solution to cardiac surgery. An effective method that replaces the function of the heart and lungs is VA-ECMO.

- Anticoagulants (e.g. LMWH) are recommended for thromboembolism prophylaxis.

- After the acute phase subsides, we switch to the medication of chronic left-sided heart failure.

Acute right-sided failure[edit | edit source]

- Treatment of the cause (pulmonary embolism, pneumothorax, cardiac tamponade, status asthmaticus,...).

![]() Morphine, recommended for use in patients with acute heart failure and severe shortness of breath (causes venodilatation, mild arteriodilation and decreases heart rate), must be indicated with caution in the presence of respiratory acidosis and COPD, as it has a depressant effect on the respiratory center and its use can therefore be lethal [1]

Morphine, recommended for use in patients with acute heart failure and severe shortness of breath (causes venodilatation, mild arteriodilation and decreases heart rate), must be indicated with caution in the presence of respiratory acidosis and COPD, as it has a depressant effect on the respiratory center and its use can therefore be lethal [1]

Treatment of chronic heart failure[edit | edit source]

Treatment of decompensation of chronic heart failure corresponds to acute heart failure.

Regime and dietary measures[edit | edit source]

- Daily monitoring of body weight - in the event of a sudden increase (2 kg in 3 days), an increase in diuretics is necessary.

- It is necessary to limit the intake of salt (up to 5 g per day), possibly liquids (up to 1.5–2 l/day) and alcohol (the tolerated amount is 1 beer or 2 dl of wine).

- Abstinence from smoking.

- Obese patients should reduce their weight.

- When traveling, it is recommended to use short flights instead of long journeys by car or bus and avoid hot landscapes with high humidity.

- Vaccination against influenza and pneumococci is recommended.

Pharmacotherapy of HFrEF (heart failure with reduced ejection fraction)[edit | edit source]

Symptomatic drugs[edit | edit source]

- Diuretics – indicated in patients with fluid retention

- Klitschko : furosemide

- Thiazide : hydrocholothiazide, chlorthalidone

- Potassium-sparing : amiloride – in patients who, despite treatment with ACE-i or sartans, have a tendency to hypokalemia

- Digoxin ( positive inotropic, antiarrhythmic, and vagotonic effects ) – in patients with chronic heart failure with atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response

Medicines improving the prognosis[edit | edit source]

- ACEI ( vasodilation, excretion of Na + and water - pressure reduction ) – enalapril, captopril

- Undesirable effects of ACEI administration can be hypotension, hyperkalemia, skin exanthema, dry cough.

- Blockers of AT 1 receptors for angiotensin II (sartans) - losartan, valsartan - indicated in case of contraindication or intolerance of ACEI

- Beta-blockers – bisoprolol, carvedilol, metoprolol ZOK (with zero-order kinetics), nebivolol

- Aldosterone receptor blockers – spironolactone, eplerenone

- ARNI - dual inhibitors of the AT1 receptor and neprilysin - sacubitril/valsartan - are a new group of drugs that prevent BNP degradation and are indicated as a replacement for ACEI in the case of insufficient optimally adjusted ACEI treatment, Beta-blockers and aldosterone receptor blockers

- Ivabradine ( reduction of TF ) – indicated in patients who do not tolerate beta-blockers or their sufficient dose to achieve TF below 75/min

- Hydralazine and isosorbide dinitrate may be considered in symptomatic patients intolerant of ACEIs or sartans

| Principles of treatment of chronic heart failure | ||

|---|---|---|

| DEGREE OF SEVERITY | THE DRUG OF CHOICE | |

| 1. | Asymptomatic left ventricular dysfunction of cardiac non-ischemic etiology (NYHA I, EF 20–40%) | ACE-I |

| 2. | Asymptomatic left ventricular dysfunction of cardiac ischemic etiology (NYHA I, EF 20–40%) | ACE-I + BB+ ASA |

| 3. | Symptomatic diastolic dysfunction of non-ischemic etiology (NYHA II-III, EF > 40%) | ACE-I + diuretics (BB?, Verapamil?) |

| 4. | Symptomatic diastolic dysfunction of ischemic etiology (NYHA II–III, EF > 40%) | ACE-I + BB + ASA + diuretics |

| 5. | NYHA II–III, EF 20–40% | ACE-I + BB + diuretics (Digitalis for atrial fibrillation and/or III. echo) |

| 6. | NYHA II–III, EF < 20% | ACE-I + BB + diuretics + digitalis + spironolactone (anticoagulation?) |

| 7. | NYHA IV | ACE-I + BB + diuretics + digitalis + spi-ronolactone + nitrates? + anticoagulation? + dopamine? + another iv? |

| 8. | NYHA IV, EF < 20%, VO2max < 14 ml/min/kg, age < 60 years | A likely candidate for a heart transplant |

| ACE-I = angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, BB = beta-blockers, ASA = acetylacylic acid | ||

| taken from [1] | ||

Pharmacotherapy of HFpEF and HFmrEF[edit | edit source]

EBM therapeutic options for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction are currently limited. Diuretics usually relieve congestion and heart failure symptoms. Anticoagulants must be given to patients with atrial fibrillation.

Invasive treatment[edit | edit source]

In patients in whom heart failure is the result of a structural disorder, the most common treatment is myocardial revascularization. Heart valve surgery, pericardectomy for constrictive pericarditisare also possible.

Cardiac resynchronization therapy ( biventricular pacing ) is used in patients with advanced heart failure with a low ejection fraction <35% and a wide QRS complex or echocardiographically confirmed myocardial contraction dyssynchrony. ICD implantation is suitable for patients with a high risk of sudden cardiac death. In some patients, biventricular stimulation is combined with an ICD - the so-called CRT-D.

Mechanical heart support - LVAD (left ventricular assist device) and BiVAD (biventricular) - are used as bridging to heart transplantation, but also today as a definitive solution.

For patients who have exhausted all other treatment options, a heart transplant is the next step.

Treatment of cardiogenic shock[edit | edit source]

- Treatment of the cause and prevention of shock:

- AMI – percutaneous coronary intervention or thrombolysis,

- pulmonary embolism – thrombolysis,

- cardiac tamponade – pericardiocentesis.

- Pharmacological support of circulation (vasoactive substances):

- dopamine, dobutamine, in their failure noradrenaline,

- Mechanical support of circulation ( intra-aortic balloon counterpulsation ).

Prognosis[edit | edit source]

Half of patients with chronic heart failure die within eight years of diagnosis. Half of patients with chronic heart failure who are permanently in functional group NYHA IV die within two years of reaching this stage.

| Estimation of prognosis according to the NYHA classification | ||

|---|---|---|

| NYHA | mortality within 1 year (%) | average survival (years) |

| AND | <5 | >10 |

| II | 5-10 | 7 |

| III | 10-20 | 4 |

| IV | 20-40 | 2 |

| taken from | ||

Links[edit | edit source]

External links[edit | edit source]

Reference[edit | edit source]

- ↑ a b c ŠPINAR, J, et al. Doporučení pro diagnostiku a léčbu chronického srdečního selhání [online]. [cit. 2013-10-03]. <http://www.kardio-cz.cz/index.php?&desktop_back=hledani&action_back=&id_back=&desktop=clanky&action=view&id=90>.

- ↑ a b c d ČEŠKA, Richard, ŠTULC, Tomáš, Vladimír TESAŘ a Milan LUKÁŠ, et al. Interna. 3. vydání. Praha : Stanislav Juhaňák - Triton, 2020. 964 s. ISBN 978-80-7553-780-5.

- ↑ a b c J. Špinar, et al., Summary of the 2016 ESC Guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Prepared by the Czech Society of Cardiology, Cor et Vasa 58 (2016) e530–e568, jak vyšel v online verzi Cor et Vasa na http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0010865016300996

- ↑ ČEŠKA, Richard, et al. Interna. 1. edition. Praha : Triton, 2010. 855 pp. pp. 19. ISBN 978-80-7387-423-0.

Source[edit | edit source]

- PASTOR,. Langenbeck's medical web page [online]. [cit. 2009]. <https://langenbeck.webs.com/>.

- Přednáška Prof. F. Kölbla, pro 4. ročník všeobecného lékařství, říjen 2007, 2. lékařská fakulta,

References[edit | edit source]

- ČEŠKA, Richard, et al. Interna. 1. edition. Praha : Triton, 2010. pp. 855. ISBN 978-80-7387-423-0.