Adrenal glands

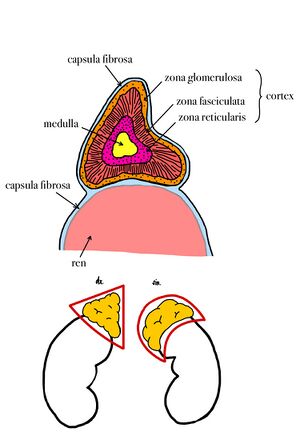

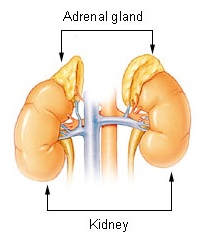

Adrenal glands are a pair of endocrine glands. They are located at the upper pole of the kidneys and in its fatty capsule. Their mass is about 8 g. On the surface there is a capsule of dense collagenous connective tissue from which the septum extends. Attached to this connective tissue are reticular fibres providing support to the parenchyma cells. The adrenal glands are composed of cortex and medulla. The cortex and the medulla are different in structure, function and origin.

- Cortex, originating from the mesodermal coelomic epithelium, produces steroids;

- Medulla, originating from neuroectoderm neural crest, produces catecholamines.

The blood supply comes by way of three arteries: superior, middle and inferior suprarenal artery. They further branch to form the subcapsular plexus, from which the arteries of the capsule and the arteries of the cortex, which anastomose throughout the cortex, are further formed and enter the veins of the marrow. This arrangement is of functional importance because glucocorticoids flowing from the cortex into the marrow act enzymatically to convert norepinephrine into adrenaline. Regulation of adrenal cortical hormone secretion is provided by adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) from the adenohypophysis.

Position and syntopy[edit | edit source]

The adrenal glands are located retroperitoneally at the upper poles of the kidneys at the level of Th11. Due to the lower position of the right kidney, the right adrenal gland is also located lower. Dorsally the adrenal glands insist on the diaphragm, ventrally the liver is in front of the right adrenal gland and the pancreas and stomach in front of the left.

Macroscopic structure[edit | edit source]

On the gland we recognize the facies anterior, facies posterior and facies renalis (renal surface). The right adrenal gland is triangular in shape, the left is crescentic. The gland is embedded in a connective sheath (capsula fibrosa) that sits firmly against the organ surface. From this sheath, a septa containing weak arteries lead into the gland.

Microscopic structure[edit | edit source]

Cortex[edit | edit source]

About 70% of the volume of the entire gland is cortex, producing about 30 steroid hormones. The adrenal cortex synthesizes two groups of steroid hormones that belong to the corticosteroids, namely glucocorticoids (e.g. cortisone), which regulate carbohydrate and protein metabolism, and mineralocorticoids (e.g. aldosterone), which control mineral and water management. Smaller amounts of sex hormones are also produced in the adrenal cortex.[1]

The cells here are arranged in trabeculae surrounded by blood sinusoids. The cells of the adrenal cortex have the characteristics of steroid-secreting cells; they have a spherical, centrally placed nucleus, in the cytoplasm we can find a massively developed smooth endoplasmic reticulum, numerous mitochondria of tubular type and lipid droplets. The cells of the adrenal cortex do not accumulate secretory products in granules. According to the arrangement of the trabeculae, the adrenal cortex is divided into three concentric layers, which in man are not precisely delimited. The individual layers are called the zona glomerulosa, zona fasciculata and zona reticularis.

- Zona glomerulosa is located just beneath the connective tissue capsule. The cells are cylindrical or pyramidal cells and form arcuate, club-like rays that are surrounded by numerous capillaries. The cells produce mineralocorticoids, especially aldosterone.

- Zona fasciculata occupies 65% of the volume of the adrenal cortex and consists of radially running trabeculae of cells. The cells are polyhedral in shape and contain a large number of lipid droplets in the cytoplasm. They produce glucocorticoids, such as cortisol, and small amounts of androgens.

- Zona reticularis is composed of cells that are arranged in irregularly anastomosing trabeculae. The cells are smaller compared to the previous layers, in some of them we find a nucleus of irregular shape, the cytoplasm contains a large amount of lipofuscin. The secretory granules of this layer contain mainly androgens and, to a minor extent, glucocorticoids.[2]

Medulla[edit | edit source]

The adrenal medulla consists of irregularly shaped trabeculae between which the capillary sinusoids pass. The medulla originates from the neural crest, and therefore its cells can be thought of as modified postganglionic sympathetic neurons. In the cells of the medulla we find chromaffin and argentaffin granules, containing mainly catecholamines.[2] The marrow contains A-cells and N-cells. A-cells produce adrenaline, which was first discovered and accounts for 80% of the catecholamines secreted into the blood. Adrenaline is secreted by nervous stimuli, especially during physical or mental stress, i.e. in stressful situations that trigger an alarm response in the body; it causes an increase in the concentration of glucose, lactate and free fatty acids in the blood.[1] N-cells produce noradrenaline, which causes blood vessels (except cardiac vessels) to contract, thereby increasing blood pressure.

Functions of adrenal hormones[edit | edit source]

Mineralocorticoids[edit | edit source]

They maintain the body's ionic balance. They are mainly active in the distal tubules of the kidneys, in the lining of the stomach, and in the salivary and sweat glands. Aldosterone affects the tubules of the kidneys and increases sodium reabsorption. Excessive aldosterone concentration can cause hypertension.

Glucocorticoids[edit | edit source]

They have a complex effect on the body's metabolism. They interfere with carbohydrate, protein and lipid metabolism. Due to their immunosuppressive effect, they suppress the immune response and stimulate gluconeogenesis and glycogen synthesis in the liver. They have a catabolic effect on other tissues outside the liver (especially proteins). They cause a decrease in the number of eosinophilic granulocytes and circulating immunocompetent lymphocytes.

Androgens[edit | edit source]

They are similar to sex hormones. Their production is low and therefore they do not play a significant role in the body. The best known is called dehydroepiandrosterone, which has mild masculinizing and anabolic effects. Pathologically, an excess synthesis of this hormone can manifest itself in women with a virilizing effect, or cause precocious puberty (pubertas precox).

Catecholamines[edit | edit source]

Emotional reaction (fear) causes the production of large amounts of catecholamines, which cause vasoconstriction, hypertension, and an increase in heart rate. We can classify these as a component of the defensive response.

Vascular supply[edit | edit source]

- Arteries: The source of blood is usually the superior suprarenal artery (a branch of the Inferior phrenic artery.), the medium suprarenal artery (a direct branch from the abdomen aorta), and the inferior suprarenal artery (a branch of the renal artery). Numerous blood vessels penetrate the adrenal gland along the entire surface of its cortex and form a succapsular plexus, the plexus subcapsularis, inside. The capsular, cortical and medullary arteries branch off from the subcapsular plexus. The medullary arteries extend in tracts to the medulla, where they break up into a network of capillaries and sinusoids.

- Veins: They join into the suprarenal veins, which emerges from the hilum on the ventrolateral side, and to the right and left, respectively, into the inferior vena cava and the renal vein.

- Nerves: Coming from the suprarenal plexus, these are mixed fibres. The cortex is mainly supplied by postganglionic fibres, the medulla by preganglionic fibres.

- Lymphatic capillaries: Located in the capsule, cortex and medulla, and accompanies the suprarenal vein, it enters the lumbar lymph nodes.[3]

Adrenal disorders[edit | edit source]

Chronic insufficiency; Morbus Addisoni (hypofunction of the adrenal cortex):

- Primary insufficiency may be caused by autoimmune disorder, inflammation, or tumor. Patients are weak, weak, lose appetite and lose weight. They develop constipation or diarrhoea, abdominal or muscle pain, bradycardia, blood pressure and lower glycemia. Characteristic pigmentation develops on irritated areas of the body, such as the dorsa of the last digits of the fingers, lines on the palm of the hand, etc. The skin is brown to grey in colour and graphite spots may be found on the mucous membranes. The pigmentation occurs as a result of increased secretion of ACTH, which has certain amino acids in common with melanocyte-stimulating hormone. A deficiency of aldosterone leads to a loss of Na and with it Cl and water, and to the retention of K.

- Secondary insufficiency occurs in hypothalamo-pituitary insufficiency, such as pituitary dwarfism. The skin is pale due to ACTH deficiency, and patients do not find disruption of the salt economy because aldosterone secretion depends on ACTH only under stress.

- The Iatrogenic insufficiency is transient, from attenuation of the adrenal cortex during long-term pharmacological administration of glucocorticoids. The patient becomes an addisonic masked by cushigoid appearance.

Acute failure

- Acute failure occurs with hemorrhage into the adrenal gland in a newborn after birth trauma, especially in hemorrhagic diathesis. It manifests as a shock state with tachycardia, high temperature, rapid breathing and cold extremities. It is often confused with severe pneumonia or septic condition. The kidney capsule is filled with blood, so careful palpation should be used to look for a tumour in the abdomen, and erythrocytes, haemoglobin, Na, K and plasma glucose should be examined.

- Acute failure also occurs with necrosis of the adrenal glands and bleeding into them during infection, usually meningococcal sepsis, the so-called Waterhouse-Friderichsen syndrome. Shock symptoms with hyperpyrexia and rapidly progressive hemorrhage into the skin are prominent.

- Adrenogenital syndrome results from the overproduction of adrenal androgens or estrogens.

Diagnosis of hypocorticalism

- The diagnosis of hypocorticalism is based on the plasma Na:K ratio in the acute state (normally around 30, in crisis around 20); hematocrit and urea rise with dehydration. Signs of hyperkalaemia on ECG and plasma cortisol determination may be valuable.[4]

Sources[edit | edit source]

Related articles[edit | edit source]

External links[edit | edit source]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ a b KODÍČEK, Milan. Biochemické pojmy : výkladový slovník. 1. edition. VŠCHT, 2004. pp. 171. ISBN 80-7080-551-X.

- ↑ a b KONRÁDOVÁ, Václava – UHLÍK, Jiří – VAJNER, Luděk. Funkční histologie. 1. edition. H+H, 1998. pp. 363. ISBN 80-86022-35-8.

- ↑ ELIŠKOVÁ, Miloslava – NAŇKA, Ondřej. Přehled anatomie. 1. edition. Karolinum, 2006. pp. 309. ISBN 80-246-1216-X.

- ↑ HOUŠTĚK, Josef. Dětské lékařství : učebnice pro lékařské fakulty. 3. edition. Avicenum, 1990. pp. 499. ISBN 80-201-0032-6.

Bibliography[edit | edit source]

- ČIHÁK, Radomír – GRIM, Miloš. Anatomie. 2. upr. a dopl edition. Grada Publishing, 2002. vol. 2. pp. 470. ISBN 80-247-0143-X.

- ELIŠKOVÁ, Miloslava – NAŇKA, Ondřej. Přehled anatomie. 1. edition. Karolinum, 2006. pp. 309. ISBN 80-246-1216-X.

- HOUŠTĚK, Josef. Dětské lékařství : učebnice pro lékařské fakulty. 3. edition. Avicenum, 1990. pp. 499. ISBN 80-201-0032-6.

- KODÍČEK, Milan. Biochemické pojmy : výkladový slovník. 1. edition. VŠCHT, 2004. pp. 171. ISBN 80-7080-551-X.

- KONRÁDOVÁ, Václava – UHLÍK, Jiří – VAJNER, Luděk. Funkční histologie. 1. edition. H+H, 1998. pp. 363. ISBN 80-86022-35-8.

- JUNQUEIRA, L. Carlos – CARNEIRO, Chosé. Základy histologie. 7. edition. H&H, 1999. ISBN 8085787377.

- GRIM, Miloš – DRUGA, Rastislav. Základy anatomie. 1. edition. Galén, 2005. ISBN 8072623028.

- PAULSEN, Douglas. Histologie a buněčná biologie : opakování a příprava ke zkouškám. 1. edition. H & H, 2004. ISBN 80-7319-024-9.