Central venous access

This article discusses the general issue. Pediatric catheterizations are discussed in the article Central vein cannulation (pediatrics)

Central venous access is access to the basin of the superior or inferior vena cava by cannulation of some major tributary. In some cases, the central river can be cannulated even through the peripheral veins on the HK.

Indication of inputs[edit | edit source]

Central venous access is most often needed for the introduction of a central venous catheter (CVI) . Approximately 8% of hospitalized patients require the insertion of a CVI during hospitalization.

Other reasons may be:

- caval filter insertion,

- insertion of a Swan-Ganz catheter,

- introduction of a pacemaker,

- vein stenting,

- venous thrombolysis,

- cannulation for extracorporeal circulatory support.

CVI indication[edit | edit source]

- Ensuring reliable long-term venous access with the possibility of applying high volumes,

- large volume replacements (in a longer time horizon),

- application of parenteral nutrition,

- administration of catecholamines or intravenous antihypertensives ,

- administration of substances that irritate the vein wall (cytostatics),

- application of high osmolar solutions,

- extracorporeal elimination methods (dialysis, plasmapheresis, CRRT, hemoperfusion) and others (ECMO) (a special type of catheter is required),

- insufficient peripheral input or the impossibility of peripheral cannulation,

- central venous pressure monitoring ,.

Contraindications[edit | edit source]

They are always relative - you have to weigh the benefit versus the risk, ideally try to remove the contraindication before the puncture (correction of coagulation, use of USG, calling in a more experienced doctor, choosing a different injection site, etc.). Contraindications include:

- hemostasis disorder (coagulopathy, thrombocytopenia) (it is better to choose access to a compressible vein, i.e. jugular vein or femoral vein, puncture under USG control),

- difficulties at the injection site:

- infection, injury, anatomical abnormalities,

- thrombosis in a punctured vein,

- another intravenous structure (another catheter, pacemaker, ...),

- little experience of the doctor and nursing staff.

History[edit | edit source]

- 1929 – Werner Forssmann was the first to insert a central venous catheter into himself and then into a patient with peritonitis. The injection was carried out in the basin of the axillaris vein or in the cubital fossa, the location of the catheter tip was checked using an X-ray.

- Misunderstood in his time, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine in 1956.

- 1950 – Aubaniac – the first cannulation in the subclavian vein. Doctors gradually joined in with cannulation, first in the femoral vein , later in the jugular vein.

- 1953 – Seldinger technique.

- Early 1970s – development of the central venous catheter in connection with the development of parenteral nutrition.

- Late 1970s – clear indications and contraindications for the use of a central venous catheter were accepted.

- End of the 20th century – development of multi-way catheters and new materials.}}

Topography, approaches[edit | edit source]

The injection site is chosen individually according to the situation, the advantages and disadvantages of the given approach in the context of the patient and the doctor's experience. The most common method of introduction is the Seldinger technique , i.e. puncture of a vein with a needle, introduction of a wire guide through the needle, removal of the needle, dilation of the channel with a plastic dilator pushed over the guide wire, introduction of a catheter.

Access can be used via:

- subclavian vein – comfortable for the patient, suitable for long-term access, the vein does not collapse even with hypovolemia, difficult to compress in case of bleeding complications, risk of PNO;

- internal jugular vein – lower risk of PNO and malposition;

- v. femoralis – suitable as an emergency entry, greater risk of infectious complications and worse for nursing care;

- veins on the arm - can be used for peripheral access to the central riverbed.

Advantages, disadvantages, indications, contraindications and implementation of specific access points

Subclavian vein[edit | edit source]

Access most often infraclavicular, possibly also supraclavicular (less common):

- lateral infraclavicular approach (outer third of the clavicle) – more advantageous than the medial approach (greater distance from the airways, longer puncture channel, but higher risk of unwanted puncture of the artery);

- medial infraclavicular approach (in the midline);

- supraclavicular approach (almost abandoned due to risk of pneumothorax and short puncture channel).

- Advantages – the subclavian vein does not collapse even during hypovolemic shock and is therefore easy to puncture, it is easier to treat, the inserted cannula causes less discomfort to the patient, a longer puncture channel reduces the risk of per continuities transfer of infection. Access through the left subclavian vein is suitable for cardiac access for pacemaker electrodes or a pulmonary catheter. Subclavian approaches are also a convenient location for a long-term subcutaneous port.

- Relative contraindications – pulmonary emphysema, injection site infection, clavicle fracture. The approach is not suitable for larger caliber catheters, especially rigid catheters for acute hemodialysis due to the bend between the subclavian vein and the brachiocephalic vein, mainly because of the risk of perforation.

- Complications – pneumothorax, hemothorax by perforation of the subclavian artery, air embolism, brachial plexus injury, tracheal puncture, thoracic duct puncture (when approaching from the left).

Internal jugular vein[edit | edit source]

On the lateral side of the neck, more approaches (anterior, posterior, central), for example, between the sternal and clavicular portions of the sternocleidomastoideus muscle.

- Advantages – relatively lower risk of pneumothorax, small risk of malposition (so it is often used in case of the need for certain quick access with the correct position of the catheter - acute administration of drugs, transvenous cardio stimulation). Cannulation of the right VJI is suitable for acute cannulation for hemodialysis or pulmonary catheterization in a straight direction without bends. The position enables compression in case of bleeding complications or puncture of an artery.

- Disadvantages – a shorter puncture channel with an increased risk of infection transfer, worse conditions for treatment and more inconvenience to patients.

- Contraindications – enlarged thyroid gland (goiter).

Arm veins[edit | edit source]

One of the access options is also infraclavicular puncture of the axillary vein using a similar technique as in the case of infraclavicular puncture of the subclavian vein. This is a newer approach that can be considered as an alternative to lateral subclavian vein puncture. [1].

For peripheral access to the central vein, it is possible to use the veins in the cubital fossa - the mediana cubiti vein, the brachialis vein - the ulnar side of the forearm are suitable , the introduction of the catheter can be difficult due to the presence of venous valves and a special monoluminal long catheter must be used. In the Czech Republic, it is used rather rarely, usually for long-term access, the advantage of the peripheral approach is the absence of complications specific to central venous cannulation (see the next chapter - PICC ).

Femoral vein[edit | edit source]

Usually a less used option due to a higher risk of thrombosis or infection. It is punctured below the inguinal ligament medial to the pulsating artery. It is a standard site for cannulation of one of the VV ECMO cannulas .

- Advantages – relatively easily accessible use as an emergency entrance without the risk of pneumothorax. Its insertion does not interfere with ongoing cardiopulmonary resuscitation (however, care must be taken during insertion to avoid mistaking an artery for a vein, as pulsation may be present in the femoral vein during CPR). It may also be beneficial in cases of upper body trauma or insufficient operator experience.

- Disadvantages – high risk of infection (although according to new research with high standards of nursing care it is comparable to other inputs) and thrombosis, it should be left only for as long as necessary. If possible, a non-femoral approach to the central vasculature is preferred, mainly because of the risk of thrombosis.}}

Types of central venous catheters[edit | edit source]

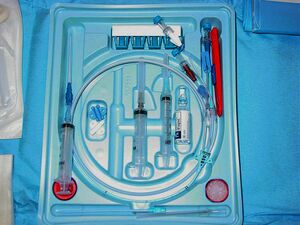

Depending on the intended use of the catheter, different techniques or types of catheters are used. For short-term use, non- tunneled catheters are used (standard catheter in Fig. 1, 2 and 4). Specific types of non-tunnelized catheters are hemodialysis catheters (solid, two lumen, Fig. 5) and sheaths used for introducing other intraluminal instruments.

Long-term and medium-term inputs[edit | edit source]

With long-term use of central venous access, various types of permanent catheters are inserted. The most common types are PICCs, tunneled catheters, and subcutaneous ports.

PICC (peripherally inserted central catheter) is a peripherally inserted central venous catheter (see Fig. 6). It is introduced into the peripheral veins of the forearm, for example in the median cubiti vein. The advantage is the possibility of medium-term (3-12 months) administration of drugs and the absence of risks typical for the introduction of central catheters (artery puncture, pneumothorax). The disadvantage is the high risk of malposition or insertion failure and the high frequency of infectious complications.

When implanting a tunneled catheter (e.g. Broviac, Hickman, diagram see Fig. 7), a standard central catheter is introduced through the appropriate approach, but further it is tunneled in the subcutaneous tissue and exits the subcutaneous tissue through an extended covered channel. It is usually secured by a cuff that grows into the subcutaneous tissue. In this way, it is protected against the introduction of infection into the riverbed and can be used for up to a few years.

The introduction of a central venous port (Figs. 8, 9 and 10) allows an even longer time of use (several years) compared to previous modalities. A central venous catheter is connected to a port that is implanted in a pocket under the skin, usually in the chest wall.

Procedure, execution[edit | edit source]

Preparation[edit | edit source]

Before the puncture itself, sufficient preparation must be ensured, including signing the informed consent and explaining the course of the procedure to the conscious patient, monitoring and appropriate positioning. Trendelenburg position facilitates puncture (filling of jugular and subclavian veins), CAVE! in patients with increased intracranial pressure, this position increases intracranial pressure even more! Furthermore, it is not always tolerated by obese or critically ill patients. This position also reduces the risk of air embolism. It is necessary to choose a suitable injection site, or to clarify the topography of the injection site in advance using ultrasound. According to local customs, the catheter is flushed with a sterile solution before use, so that it does not cause an air embolism if inserted incorrectly.

Antibiotic prophylaxis is not considered standard practice.

Use of ultrasound[edit | edit source]

Ultrasound monitoring can be used to visualize potential injection sites prior to cannulation. During self-cannulation, ultrasound control reduces the risk of complications and speeds up the time required for cannulation. If it is impossible to use ultrasound for cannulation, topographical "landmarks" are used according to the above-mentioned descriptions. After successful cannulation, ultrasound can be used to preliminarily check the position of the catheter tip or possible complications (pneumothorax, arterial puncture).

Puncture procedure[edit | edit source]

This chapter describes general access to the vascular bed for non-tunneled catheters.

Step by step procedure

- We will prepare the operating field using aseptic technique - disinfection, sterile cover, mask over the mouth, hair cover, sterile gloves and gown.

- We will clarify with the help of ultrasound or anatomical "landmarks" the injection site.

- We will provide sufficient local anesthesia or sedation.

- We cannulate the vein with an introducer needle, usually under vacuum in a syringe, preferably using ultrasound guidance.

- We introduce a guide wire (Seldinger method) under ECG control (the tip of the catheter can negatively irritate the myocardium and cause tachycardia, fibrillation). If the cannulation is performed under ultrasound control, we check the position of the guide wire in the given vein and its further course (for example, during cannulation of the right subclavian vein, both VJIs can be checked for malposition).

- We remove the needle to check the position of the guide wire.

- We make a small skin incision next to the guide wire entry point.

- We introduce a dilator along the wire to dilate the subcutaneous channel. We will remove the dilator again after checking the wire.

- We introduce a catheter along the wire. Before inserting the catheter into the subcutaneous channel, enough of the guide wire should be withdrawn to allow it to be passed through the entire catheter and grasped at the end. We introduce the catheter through the subcutaneous channel into the central vein and check the end of the guide wire with the other hand (if not observed, it could happen that we insert the wire together with the catheter into the vein).

- We remove the guide wire while checking the position of the catheter.

- We will check the patency of all catheter lumens. First, it is necessary to aspirate (especially if it is not customary to flush the catheter site before use), then flush the lumen with a sterile solution (e.g. F 1/1).

- We fix the catheter to the skin with atraumatic stitches.

- We connect the infusion sets or sterilely close the currently unused lumens.}}

Catheter tip position check[edit | edit source]

At a distance, we check the position of the tip and post-puncture complications (pneumothorax) by standard X-ray. Routine radiodiagnosis is not necessary for femoral catheters, and some studies question its use even for uncomplicated right VJI puncture.

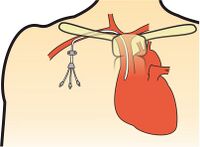

The ideal placement of the catheter tip is a matter of debate and depends on the puncture site used. It should be placed in a large vessel (superior or inferior vena cava) and not extend into the right atrium. Insertion that is too deep can cause perforation of the wall and subsequent tamponade, possibly lasting arrhythmia. Catheter malposition can also lead to misinterpretation of central venous pressure readings. Prof. In his textbook, Ševčík therefore recommends the position of the catheter tip in the cavo-atrial junction. [2]. Inspection may reveal a malposition, for example, with the tip of the catheter upward in the VJI during cannulation of the subclavian vein.

Specific types of catheters[edit | edit source]

In the case of long-term inputs, tunneling is preferred, i.e. the extension of the subcutaneous course of the cannulation channel, or the implantation of a subcutaneous port, as described in the chapter above. In these cases, the actual cannulation takes place similarly, but a subcutaneous channel is also created for the course of the catheter, or a pocket into which a sterile subcutaneous port is placed.

Insertion ports are also introduced using a similar procedure, for example for the insertion of caval filters.

Catheter removal[edit | edit source]

The following should be observed when removing the catheter:

- removal of the catheter in a suitable position (for example, reverse Trendelenburg - elevated head) and during exhalation to prevent air embolism,

- sending the tip of the catheter for microbiological examination,

- disinfection and sterile dressing of the wound.

Care of an indwelling catheter[edit | edit source]

Due to the risks associated with central venous cannulation, care should be taken to:

- regular checks and dressings of the injection site,

- perform all manipulations with the catheter aseptically,

- we will remove the catheter if there are any signs of infection at the injection site.

Complications[edit | edit source]

- Complications during cannulation

- arterial puncture (subsequent hematoma with vein compression and difficult or impossible puncture), venous hematoma, punctured vein rupture, pleural injury and pneumothorax, thoracic d. injury, adjacent nerve injury, failed cannulation, arrhythmia induced by the guide wire.

- Complications of an already inserted catheter

- infections (catheter-related bloodstream infections) incl. catheter sepsis, vein thrombosis.

Video gallery[edit | edit source]

Links[edit | edit source]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ TAYLOR, B L – YELLOWLEES, I. Central venous cannulation using the infraclavicular axillary vein. Anesthesiology [online]. 1990, vol. 72, no. 1, p. 55-8, Available from <https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2297133>. ISSN 0003-3022.

- ↑ ŠEVČÍK, Pavel, et al. Intenzivní medicína. 3. edition. Galén, 2014. 1195 pp. pp. 157–161. ISBN 9788074920660.

Related Articles[edit | edit source]

- Provision of venous access

- Arterial catheter

- Artery cannulation

- Peripheral vein cannulation

- Seldinger technique

External links[edit | edit source]

- Central venous cannulation

- Central venous catheters

- Zentralvenöser Catheter

- Lecture on long-term and medium-term admissions on the website of Havlíčkův Brod Hospital

Literature[edit | edit source]

- DOEFFINGER, Joachim – JESCH, Franz, et al. Intensivmedizinisches Notizbuch. 4. edition. Wiesbaden : Abbott GMBH, 2002. ISBN 3-926035-35-8.

- HEFFNER, Allan C, et al. Overview of central venous access [online]. The last revision 2018-11-27, [cit. 2020-02-06]. <https://www.uptodate.com/contents/overview-of-central-venous-access>.

- ČIPEROVÁ, Radka. Péče o pacienta s centrálním žilním katétrem [online]. Hradec Králové : Lékařská fakulta Univerzity Karlovy v Hradci Králové, 2017, Available from <https://is.cuni.cz/webapps/zzp/download/130220907>.