Flavivirus

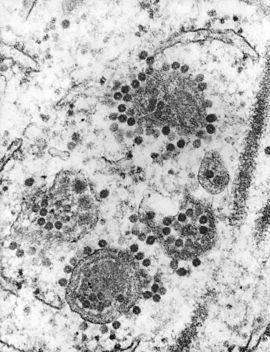

Flaviviruses are small viruses, 40-50 nm in diameter, which have a spherical lipid shell with glycoprotein protrusions. Inside the glycoprotein membrane is a cubic capsule containing a dense marrow and linear RNA. They replicate in the cytoplasm and acquire their lipid shell by budding across the membrane of cytoplasmic vacuoles.

All viruses of the genus Flavivirus belong to the Arboviruses (arthropod-borne virus), which are of different families and share the common feature of transmission by arthropods. The reservoir is vertebrate animals, among which the infection is transmitted by an insect vector.

Flaviviruses are labile, sensitive to fatty solvents and ether, and lose infectivity at temperatures above 56 °C.

- Flaviviruses are divided into four groups based on antigenic features

- viruses of the tick-borne encephalitis complex;

- virus of Japanese encephalitis;

- dengue viruses;

- yellow fever virus.

Tick-borne encephalitis complex viruses[edit | edit source]

Tick-borne encephalitis complex viruses are found with natural outbreaks in Europe, Asia and North America. The reservoir is wild mammals, the vector is ticks of various species. The individual viruses of the tick-borne encephalitis complex are antigenically related to each other but differ in the severity of the disease they can cause in humans.

- Classification of tick-borne encephalitis complex viruses

- Kyasanur Forest Disease virus (India);

- Omsk hemorrhagic fever virus (Siberia, causes severe hemorrhagic fever with CNS involvement);

- Lupus virus (Louping-ill, an epizootic of sheep in the British Isles, causes inapparent infection or mild meningoencephalitis in humans);

- Powassan virus (natural outbreaks in Canada and the USA, rarely causes infection in humans and the course of any disease is mild);

- Eastern-type tick-borne encephalitis virus (Russian spring-summer encephalitis);

- Western-type tick-borne encephalitis virus (Central European tick-borne encephalitis).

Eastern tick-borne encephalitis viruses (Russian tick-borne encephalitis)[edit | edit source]

Eastern-type tick-borne encephalitis viruses cause Russian spring-summer encephalitis in humans. They occur east of the Urals, in the Siberian taiga. In unvaccinated individuals, they cause severe meningoencephalitis, which is lethal 30 % of the time. In survivors, it can cause permanent paresis.

Western tick-borne encephalitis viruses (Central European tick-borne encephalitis)[edit | edit source]

Western-type tick-borne encephalitis viruses are found in natural outbreaks in areas west of the Urals to eastern France. In humans, they cause tick-borne meningoencephalitis. Most cases are reported in summer and autumn. In nature, rodents are the reservoir. The vector is ticks, mainly of the genus Ixodes ricinus in the Czech Republic. Ticks transmit the infection to larger wild mammals, but also to grazing domestic animals (sheep, goats, cattle), which are infected inapparently and can be a source of infection via humans, who can become infected not only after being attached to a tick in whose salivary glands the virus multiplies, but also after consuming uncooked milk into which the virus is excreted in the virulent stage. The natural outbreaks in the Czech Republic are Beroun, Strakonice, Karlovy Vary, Hradec Kralove, Brno, Olomouc and Ostrava.

- Pathogenesis

A person can be infected in the following cases:

- by the bite of an infected tick;

- ingestion of infected unpasteurized milk.

Only one third of infected persons develop overt disease. The virus enters the bloodstream from the salivary glands of the tick and primary viremia occurs, during which the meninges are not infected. The virus first enters the lymph nodes, where it multiplies and moves to other lymphoid tissues. If the infection is not eradicated by the immune system at this stage, secondary viremia occurs, when the virus enters the cerebrospinal fluid via the plexus choroideus and then the meninges, where it multiplies again. Replication takes place in the endothelium of CNS capillaries and spreads progressively to CNS tissues, where all cell types can be infected.

- Clinical picture

The course of tick-borne meningoencephalitis is biphasic. After an incubation period (1-2 weeks), influenza-like symptoms appear. This is followed by a remission of several days, which results in a second phase of the disease with neurological symptoms. This may take different forms:

Meningitis is a localized disease of the meninges. Meningoencephalitis and encephalomyelitis have the character of panencephalitis with perivascular infiltration. The basal ganglia, the grey matter of the bulb and the cerebellar cortex are most commonly affected. The acute phase lasts 1-2 weeks, recovery is long. The prognosis is favorable, permanent consequences in the form of paralysis are rare. A lethal outcome is also rare.

- Diagnostics

Rapid diagnosis is made by serum IgM in acutely ill patients. Specific antibodies can then be demonstrated in the recovery phase. The virus can also be isolated from blood (at the viremic stage) and cultured in newborn mouse.

- Prevention

Tick-borne encephalitis is vaccinated against with a live formaldehyde-inactivated vaccine. This is a cellovirion vaccine adsorbed to aluminum hydroxide. FSME-Immun, FSME-Immun Junior (for children) and Encepur are available in our country. Vaccinations are available on request for a fee. Vaccination is especially recommended for persons at risk of infection. To achieve the necessary immunity, three basic doses are given 300 days apart (conventional vaccination schedule). A shortened schedule can also be used in which 3 doses are administered 21 days apart. Protection after vaccination occurs within 14 days. Minimum protection after complete and proper vaccination persists for at least 3-5 years, i.e. re-vaccination should be carried out every 3 years or 5 years. The tick-borne encephalitis vaccination is purely preventive and cannot be used for prophylaxis after a tick attachment.

Japanese encephalitis virus[edit | edit source]

Japanese encephalitis is a relatively rare disease found in most countries in East and Southeast Asia. Japanese encephalitis is transmitted by the bite of an infected Culex mosquito. The reservoir of infection is mainly birds, pigs and cattle. There is no human-to-human transmission. Individuals in agricultural areas of East and South-East Asia, especially children and the elderly, are at risk. Prevention is by the use of an inactivated vaccine.

- Clinical picture

Infection is mostly inapparent, but some affected individuals develop moderate to severe encephalitis. The manifestations are fever, vomiting, abdominal pain, headache, neck stiffness, speech disorders. In the most severe cases, convulsions, choking, mental disorders, coma and even death may develop.

Dengue virus[edit | edit source]

Infection with dengue viruses is endemic in tropical and subtropical regions. The reservoir is human in densely populated areas, and virus circulation is dependent on the presence of the Aedes aegypti mosquito. Jungles are another focus of infection, where monkeys are the reservoir and other mosquito species, particularly Aedes albopictus, are the vector.

- Clinical picture

Clinical signs are caused by the virus only in humans. The disease is called dengue fever and has two different forms, differing in severity:

- benign form with influenza-like symptoms;

- hemorrhagic fever with a severe course, often leading to shock and death.

Laboratory evidence is based on serological examination. There is no specific therapy or vaccine.

Yellow fever virus[edit | edit source]

Links[edit | edit source]

Related articles[edit | edit source]

External links[edit | edit source]

References used[edit | edit source]

- BEDNÁŘ, Marek. Lékařská mikrobiologie. 1. edition. Praha : Marvil, 1996. 558 pp. pp. 451.

- BENEŠ, Jiří. Studijní materiály [online]. ©2010. [cit. 15-11-2010]. <http://jirben2.chytrak.cz/materialy/infekceJB.doc>.