Serous lesions/PGS

Serate lesions (serrate lesions, serrate adenomas, serrate adenomas) are a group of adenomas of the large intestine, from which approximately one third of all colorectal cancers arise. Serate lesions were first described by Longacre and Fenoglio-Preiser in 1990 as the result of an analysis of a group of colorectal polyps with mixed features of both hyperplastic polyp and adenoma. Serous lesions have several subtypes that differ in their risk of developing malignancy. Serate lesions owe their name to the fact that the protruding epithelial cells of the crypts resemble the teeth of a saw blade in their arrangement. The basis of such an arrangement is a disorder of apoptosis in the sense of a higher resistance of cells to pro-apoptotic signals.

The molecular mechanism of the formation of serous lesions and eventual malignant tumor is different from the traditional adenoma-carcinoma pathway, which involves the mutation of the APC gene, as well as from the direct mutation of mutator genes, which is the cause of Lynch syndrome. There is talk of a serous pathway leading to carcinoma with a hypermethylation phenotype. The initiation step of the serum pathway is apparently mutations of KRAS or BRAF, protein kinases involved in the MAPK signaling pathway, and subsequently hypermethylation of CpG islands in the regulatory regions of mutator genes, the so-called CIMP phenotype (CpG Island Methylated Phenotype). This results in the suppression of the expression of repair proteins and the cell becomes more susceptible to the development of other somatic mutations. The exact sequence of mutations and disorders during the serate pathway is not known, it is likely that several partially interconnected pathways are involved.

Classification of serous lesions[edit | edit source]

The classification according to WHO (2010) is as follows:

- hyperplastic polyp (HP, HPP)

- sessile serous adenoma/ polyp1 (SSA/P)

- — without cytological dysplasias

- — with cytological dysplasias (SAAD)

- tradiční serátní adenom (TSA)

1The terms adenoma and polyp are used, at least in English texts, as synonyms.

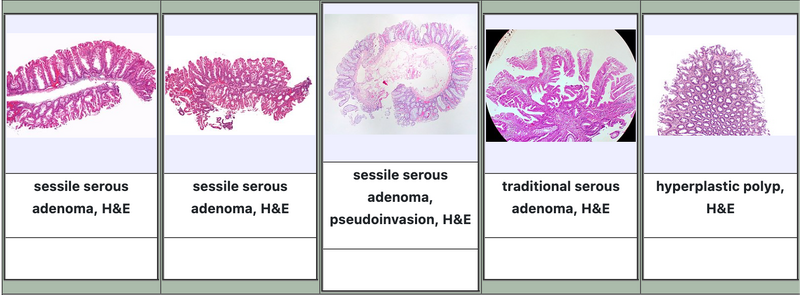

Hyperplastic polyp[edit | edit source]

Hyperplastic polyp (HP) accounts for 80-90% of all serous lesions. More than 90% occur in the rectosigmoid. Most are less than 0.5 cm, but less than one quarter of polyps are larger than 1.5 cm in diameter. A characteristic feature are straight crypts that spread symmetrically from the surface to the muscularis mucosae without significant distortion. Crypts are usually wider at the surface, the width is smaller at the base. The crypts show neither irregular nor horizontal distribution. Depending on the subtype, the crypt epithelium is accompanied by a variety of cell types. Neuroendocrine cells can often protrude at the base of the polyp. Mitoses are rather sparse, in the basal half of the crypts. Serrations are more pronounced in the upper half of the crypts and on the surface of the polyp. Cytological atypia are mostly inconspicuous, they may not be noticeable at all. The nuclei are small, oval or slightly elongated, without hyperchromasia, there are no visible signs of stratification. In some cases, herniation of the crypts through the muscularis mucosae (pseudoinvasion, inverted growth pattern) can be detected.

Histologically, HP can be divided into the following subtypes:

- microvesicular HP

- HP with goblet cells

- HP chudý na mucin

Microvesicular hyperplastic polyp[edit | edit source]

Microvesicular hyperplastic polyp is the most common variant of hyperplastic polyp. It is characterized by the presence of microvesicles, i.e. small drops of mucin, in the cytoplasm of most cells. It occurs more often in the left colon, especially in the rectum, multiple occurrences are not unusual.

Hyperplastic polyp with goblet cells[edit | edit source]

Goblet cell hyperplastic polyp is characterized by almost exclusively goblet cells being present in the wall. Serrations in the lumen are hardly noticeable with this type, or may not be captured at all. The proliferative zone is at the base of the crypts, usually limited to only a few cells. A hyperplastic goblet cell polyp is usually found in the left colon and is commonly less than 0.5 cm in diameter.

Mucin-poor hyperplastic polyp[edit | edit source]

Mucin-poor hyperplastic polyp is a rare subtype of hyperplastic polyp. It is characterized by the fact that there is at most only a small amount of mucin in the cells. Nuclei show more pronounced atypia, are larger, oval, hyperchromatic, without evident pseudostratification.

Sessile serous adenoma/polyp[edit | edit source]

Sessile serous adenoma/polyp (SSA/P), also known as sessile serous lesion (SSL), accounts for about 15–20% of serous lesions.

Macroscopically, it usually presents as a flat or only slightly elevated lesion that is more than 5 mm in diameter. It occurs more often in the right colon. Histologically, it is mainly characterized by a change in the growth pattern of the crypts. At low magnification, these changes are clearly visible as disorganization and distortion of the crypts. The crypts can be, especially in the basal parts, dilated (sometimes we talk about the bulbous shape of the crypts) and branched, sometimes the crypts can grow parallel to the muscularis mucosae, sometimes we talk about horizontal growth. Crypts can thus take on a shape sometimes described as the letter "L", "boat" or "arrow". The serration in the basal half of the crypts is quite pronounced, sometimes it is even referred to as hyperserration. Goblet cells and mucinous cells are often visible in the basal half of the crypts.[1][2]

Proliferative activity measured by monitoring the proliferative antigen Ki67 is evident along the entire length of the crypt, but Ki67 expression is often irregular and asymmetric. A varying degree of nuclear atypia may occur, sometimes dystrophic goblet cells can be seen. Neuroendocrine cells can sometimes be completely absent. Sometimes, foci of cells with an elongated or brush-like nucleus and more prominently eosinophilic cytoplasm can also be detected. Extracellular mucin production is frequent, usually prominent. It is not unusual that extracellular mucin is produced in such a quantity that it completely fills the lumen of the dilated crypt and also covers the free surface of the polyp. In the submucosa, there can sometimes be an increase in fatty tissue resembling a lipoma. Crypt herniation through the muscularis mucosae is not an uncommon finding. The diagnosis of SSA/P is established mainly on the basis of changes in tissue architecture, cytological changes are generally uncharacteristic.

SSA/P with cytologic dysplasias[edit | edit source]

SSA/P with foci of dysplastic changes (SSAD) similar to conventional tubular or tubovillomatous adenoma represent a state of progression from a polyp to a malignant tumor. Outside of areas of dysplastic change, the architecture may be quite typical of SSA/P.

Cytological changes in dysplastic areas mainly include the presence of elongated cells with amphophilic cytoplasm, whose nuclei are hyperchromatic and pseudostratified. The number of mitoses is increased.

The significance of the assessment of dysplastic changes as low-grade and high-grade is not entirely clear, most likely even low-grade dysplastic changes in SSA/P should be considered comparable to high-grade changes in conventional adenoma.

Rarely, serrate dysplasia also occurs, in which there is a proliferation of atypical cuboidal cells with eosinophilic cytoplasm and enlarged round nuclei with distinct vesicular chromatin, visible nucleoli. Mitoses are more numerous. The meaning is unclear, rather it is only assumed that this form of dysplasia is also a sign of development towards malignancy.

Traditional serous adenoma[edit | edit source]

Traditional serous adenoma (TSA) is a rare variant of serous lesions, accounting for 1–6% of all serous lesions. It has been known since 1990, when it was described as a rare variant of adenoma.

TSA is a promining or pendulous polyp, a villous appearance is also described. It is usually no larger than 1.5 cm in diameter. About 80% of TSA is located in the left colon, most often in the rectosigmum. Histologically, it is characterized by a complex tubovillous or villous to filiform configuration. A characteristic growth pattern is the budding of new crypts perpendicular to the long axis of filiform and villous structures, the so-called ectopic formation of crypts. Of course, the crypts thereby lose contact with the muscularis mucosae. TSA cells have abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm with a basal or centrally located slightly elongated nucleus with distinct chromatin structure. The epithelium usually shows signs of pseudostratification, proliferative activity is low to negligible. Foci of dysplasia similar to conventional adenoma as well as foci of serrate dysplasia may be found. These changes can be evaluated as low-grade or high-grade, roughly 90% of lesions show signs of low-grade dysplasia.

A rare variant of the traditional serous adenoma is the filiform serous adenoma, which accounts for about 4% of traditional serous adenomas, i.e. at most about 2‰ of all serous lesions. It occurs more distally and is characterized by very long to filiform villi, marked edema of the lamina propria and relatively numerous epithelial erosions. The epithelium itself is usually made up of a mixture of eosinophilic and goblet cells.

Unclassifiable serous lesions[edit | edit source]

Because of overlapping histological features or for technical reasons, it may be impossible in some cases to assign a serrate lesion to one of the categories. In these cases, the designation "unclassified serous polyp" can be used.

Conventional adenomas can sometimes contain areas in which the architecture of the tissue is rather serrate. For such a finding, the label "conventional (tubular, villous, tubovillous) adenoma with serrate differentiation pattern" can be used. The biological significance of such polyps is unclear. Mixed polyps containing several serrate patterns can sometimes occur. The following combinations have been described:

- SSA and TSA

- SSA and conventional adenoma (all types)

- TSA and conventional adenoma (all types)

- HP and conventional adenoma (all types) - a very rare combination

The following descriptions should not be used:

- circular saw polyp (der Sägeblattpolyp')

- serous polyp with abnormal proliferation

- mixed polyp from HP and SSA

serous polyposis syndrome (SPS)[edit | edit source]

The syndrome of serous polyposis, also the syndrome of hyperplastic polyposis, is characterized by the multiple occurrence of serous polyps, especially hyperplastic polyps and sessile serous adenomas. The WHO criteria for the diagnosis of SPS are met if at least one of the following conditions is met:

- at least 5 serrate polyps proximal to the sigmoid, of which at least 2 are larger than 1 cm

- any number of serous polyps proximal to the sigmoid in a patient who has a first-degree relative with hyperplastic polyposis

- more than 20 or 30 serous polyps of any size anywhere in the colon

As this is a genetic disorder, the diagnosis should be confirmed by genetic testing, endoscopic and histopathological findings should not be sufficient to confirm the diagnosis.

Differential diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Diagnostically significant characteristics[edit | edit source]

Differential diagnostically significant characteristics of individual serous lesions are summarized in the following tables.

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

Diagnostic notes[edit | edit source]

- Differences in the biological behavior of individual subtypes of hyperplastic behavior are debatable. Because their distinction is sometimes difficult, it is not useful to distinguish between individual types in routine diagnostics.[2]

- Immunochemical detection of MUC6, which has been studied as a marker to distinguish between hyperplastic polyp (MUC6 negative) and sessile serous adenoma (MUC6 positive), is a relatively specific but not very sensitive marker, so its use is not recommended.

- In the case of sessile serous adenoma, herniation (pseudoinvasion) through the muscularis mucosae must also be evaluated. If the muscularis mucosae was not captured, it is appropriate to mention this in the description. Aust et al. recommend using the term sessile serrate polyp only in these cases, but the broader consensus is that the terms sessile serrate polyp and sessile serrate adenoma are synonymous.

- The term sessile serous lesion is used by some authors to denote a sessile serous adenoma without dysplastic changes. This designation is outside the WHO classification, therefore it cannot be considered a suitable synonym.

- The distinction between the microvesicular variant of hyperplastic polyp and sessile serous adenoma is absolutely essential. There are several differential diagnostic recommendations:

- WHO 2010: At least three contiguous or at least two isolated crypts with an appearance characteristic of sessile serrate adenoma must be detected for the diagnosis of sessile serrate adenoma.

- Austl et al.: Detection of basal serration, horizontal growth of crypts, inversion (herniation) of crypts and basal dilatation of crypts in at least two crypts.

- The presence of only one characteristic crypt is probably sufficient for the diagnosis of sessile serous adenoma, and the polyp will then probably behave clinically as a sessile serous adenoma.[3]

- The differences in the patterns of immunochemical staining between the individual types of adenomas for the proliferative antigen Ki67 and cytokeratin CK20 are statistically significant, but these are signs of low sensitivity and low specificity, so their significance for routine diagnosis is considerably limited. Common patterns are as follows:

- Crypts on normal mucosa show Ki67 positivity in the basal quarter, CK20 is expressed on the surface, it does not penetrate into the crypts at all or only minimally.

- The crypts of hyperplastic polyps are positive for Ki67 up to a third to half of their length, the positivity is regular and symmetrical, the variability between the crypts of one polyp is minimal. The CK20 positivity extends deeper into the crypts, but with the decrease, the positivity decreases noticeably.

- Crypts of sessile serous adenomas (without dysplasia) are characterized by irregularity in the distribution of Ki67 positivity between individual crypts. Positivity can reach different heights, it tends to be asymmetrical. CK20 also shows irregularities incl. foci of weakly positive to negative cells on the surface. A relatively characteristic feature is CK20 positivity at the base of dilated crypts. Regions that express both Ki67 and CK20 can also appear.

- In the case of traditional serrate adenomas, Ki67 is significantly positive especially in ectopic crypts, the pattern of positivity is characterized by considerable irregularity. Conversely, CK 20, although the expression pattern may also be irregular, is limited to surface cells.

- Conventional adenomas are characterized by highly irregular expression of Ki67 and CK20.

Molecular pathology[edit | edit source]

There are at least three general genetic and epigenetic mechanisms that can lead to the development of colorectal cancer:

- chromosomal instability

- defective DNA repair leading to microsatellite instability

- epigenetic hypermethylation of CpG promoter sequences leading to the CIMP phenotype (CpG Island Methylator Phenotype)

In the case of serous lesions, the last two mechanisms apply. Physiologically, methylation of CpG promoter sequences leads to the suppression of gene expression, if the promoter sequences of tumor suppressor genes are hypermethylated, the cell is more susceptible to tumor reversal due to the accumulation of uncorrected errors. Tumors with a CIMP phenotype are often associated with a BRAF mutation, while tumors with chromosomal instability are usually associated with a KRAS mutation. The basic molecular characteristics of individual lesions are summarized in the following table:

| lesion | CpG methylation | methylation of MHL1 | microsatellite instability | mut. BRAF | mut. KRAS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| conventional adenoma | + | - | - | - | ++ |

| hyperplastic polyp | + | - | - | + | + |

| sessile serous adenoma without dysplasia | +++ | - | - | +++ | - |

| sessile serous adenoma with dysplasias | +++ | ++ | ++ | +++ | - |

| traditional serous adenoma | ++ | - | - | + (i -) | + (i -) |

| cancer with chromosomal instability | +/- | + | - | +/- | ++ |

| carcinoma associated with Lynch syndrome | - | - | +++ | - | ++ |

| carcinoma with a CIMP-high phenotype | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | - |

Molecular characteristics of individual lesions[edit | edit source]

Hyperplastic polyp[edit | edit source]

A BRAF or KRAS mutation is usually present, probably the initial mutation in most hyperplastic polyps.

Microvesicular hyperplastic polyp, which is the most common of the hyperplastic polyps, is most often characterized by the V600E mutation of the BRAF gene. This mutation leads to constitutive stimulation of the MAPK signaling cascade and thus to an increase in proliferative activity and inhibition of apoptosis. It is the apoptosis disorder that is responsible for the characteristic "sawtooth" appearance.

Sessile serous adenoma[edit | edit source]

Similar to microvesicular hyperplastic polyps, BRAF mutation appears to be the initial disorder in sessile serous adenomas. This mutation can be demonstrated in 70-80% of cases. With the progression towards dysplastic changes and cancer, p16 protein expression is suppressed through hypermethylation, thereby escaping the activation-induced aging process. Similarly, one of the typical changes of SSA, attenuation of the expression of the mutator (repair) gene MLH1, is common only in dysplastic polyps, even more so in high-grade dysplasia. Activation of the Wnt signaling cascade, which is usually associated with tumor formation through chromosomal instability, was also observed during the progression of sessile serous ademon. A decrease in β-catenin expression was observed in some sessile serous adenomas with dysplasia, but without a demonstrable mutation. Methylation of the regulatory sequences of several antagonists of the Wnt signaling cascade has been demonstrated in some sessile adenomas. Methylation of the promoter sequences of the MGMT mutator gene has been demonstrated in some sessile serous adenomas.

Because the initial mutation is usually the same, the question of the relationship between the microvesicular variant of hyperplastic polyp and sessile serrate adenoma is still unclear. Diametrically different biological behavior and different localization speak against kinship, for kinship the identical initial mutation and to a certain extent similar histological structure. It is possible that a sessile serous adenoma develops from a hyperplastic polyp only under the concurrence of several circumstances, so that reversal is unlikely.

Traditional serous adenoma[edit | edit source]

Because traditional serous adenoma is a relatively infrequent lesion, the molecular characteristics are relatively poorly described and some results are even contradictory. Compared to other serous lesions, traditional serous adenoma is perhaps characterized by higher methylation of MLH1. BRAF (55%) and KRAS (29%) mutations and MGMT expression suppression (63%) are also relatively common. In particular, KRAS mutations and MGMT attenuation appear to be more frequent in advanced lesions. A hypermethylation phenotype is demonstrable in the majority of traditional serous adenomas (79%).

Serátní dráha vzniku kolorektálního karcinomu[edit | edit source]

Three relatively broad molecular profiles of carcinomas arising from the serous pathway have been described:

- BRAF mutation and significant CpC methylation (CIMP-H)

- associated with significant microsatellite instability (MSI-H)

- associated with microsatellite stability (MSS)

- KRAS mutation and CpC low methylation (CIMP-L), microsatellite stability (MSS)

BRAF mutation with microsatellite instability represents a variant occurring in 9–12% of colorectal cancers, and is considered to be the classic pathway of a tumor derived from serous lesions. Histologically, tumors are usually poorly differentiated or mucinous, inflammatory infiltration around the tumor is common, tumor infiltrating lymphocytes are also numerous. The precursor lesion is a sessile serous adenoma, remnants of which can sometimes be found. The key event is apparently excessive DNA methylation. Attenuation of MLH1 expression is most likely responsible for the development of high-grade cytological dysplasias and microsatellite instability. The changes lead to very rapid progression to malignancy. This type of tumor is relatively resistant to non-surgical therapy, but its prognosis is relatively good.

BRAF mutation with stable microsatellites represents a variant in about 9-8% of colorectal cancers. Histologically, these are usually poorly differentiated or mucinous carcinomas. Carcinomas have a relatively large potential with lymphatic pathways and blood, and perineural spread is not uncommon. Hypermethylation is also responsible for the accumulation of mutations, but this most likely occurs through p16/Wnt suppression. The prognosis is probably poor.

KRAS mutation comprises a group of probably 15-20% of colorectal cancers. This group is still somewhat controversial. It is believed that the precursor lesion could be a traditional serous adenoma. Since the relatively high proportion of this group contrasts with the relatively rare occurrence of traditional serous adenomas, the existence of other precursors is assumed. In addition to KRAS mutation and (difficult to demonstrate) lower methylation (CIMP-L), methylation attenuation of MGMT expression is a characteristic feature.

Clinical behavior and management[edit | edit source]

Biological behavior of individual lesions[edit | edit source]

A hyperplastic polyp, especially if small, has a very low risk of progression to colorectal cancer regardless of location. Hyperplastic polyps located on the right and larger than 10 mm in diameter may have a greater potential for malignant transformation, although only case reports and small case series have been described.

A traditional serous adenoma has roughly the same risk of progression to colorectal cancer as a conventional adenoma.

Sessile serous adenoma has the potential for malignant transformation. If cytological dysplasias are also present, the malignant potential is very high.

Serous polyposis syndrome represents a significant risk of developing colorectal cancer.

Management of serous lesions[edit | edit source]

The prevailing consensus is that all serous lesions should be removed colonoscopically. The exception is only minor hyperplastic rectosigmoid polyps, where it is sufficient to take a few random samples for histological examination. Lesions smaller than 10 mm are better treated with a sharp technique, larger lesions can also be treated with electrocautery. The edges of a serous lesion may not be clearly visible, so it is sometimes appropriate to use contrast enhancement techniques such as mucosal staining, submucosal injection of a contrast agent, or special lighting. Removal of serous lesions can be very difficult or impossible if they are located in the mouth of the appendix or on the ileocecal valve.[1]

Surgical resection of part of the intestine is rarely necessary. It may be suitable in cases where the serous lesion cannot be treated endoscopically. Surgical resection is also considered in case of multiple serous lesions in the proximal colon.

The ability of both sessile serous adenoma and traditional serous adenoma to turn into a tumor is fairly well demonstrated at the molecular level. At the clinical level, only case reports and studies following only a small number of patients are available, so current knowledge is relatively limited. Therefore, recommendations and information about factors that predict further biological development must be approached with relative caution.

The main factors identified so far that influence the prognosis of further development, i.e. the risk of turning into colorectal cancer, are the following:

- Histological subtype: SSA and TSA have a significantly higher risk than HP. The significance of dysplastic changes in SSA and TSA is not entirely clear, but it is likely that they represent a higher risk than SSA and TSA respectively. TSA without dysplastic changes.

- Number of polyps: A higher number of polyps is a risk factor for both the development of new polyps and malignant transformation.

- Co-occurrence of conventional adenomas: This is thought to be a higher-risk condition, but direct evidence is lacking.

- Location: The occurrence of SSA in the distal colon is uncommon, but the prognostic significance is unknown.

- Polyp size: The size of the serous lesion is a likely prognostic marker. E.g. the value of 10 mm for SSA is somewhat arbitrary and it is possible that this limit will be changed.

There are several recommendations for monitoring and repeating checks:

| subtype | size | number | localization | check interval |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HP | <10 mm | Any | rectosigmoid | population screening / 10 years |

| HP | ≤5 mm | ≤3 mm | proximal to the sigmoid | population screening / 10 years |

| HP | Any | ≥4 mm | proximal to the sigmoid | 5 years |

| HP | >5 mm | Any | proximal to the sigmoid | 5 years |

| SSA/TSA | <10 mm | <3 mm | anywhere | 5 years |

| SSA/TSA | ≥10 mm | Any | anywhere | 3 years |

| SSA/TSA | <10 mm | ≥3 mm | anywhere | 3 years |

| SSA/TSA | ≥10 mm | ≥2 mm | anywhere | 1–3 years |

| SSA with dysplasia | Any | Any | anywhere | 1–3 years |

| subtyp | risk of developing cancer | check interval |

|---|---|---|

| HP | it isn't | further checks are not indicated |

| SSA | is, the severity is unknown!! 3 years | |

| TSA | is, the same or possibly even higher than conventional adenomas | 3 years |

| mixed polyp | is | 3 years |

If complete removal has not occurred, follow-up endoscopy should follow 2 to 6 months after the procedure.

Links[edit | edit source]

Virtual preparations[edit | edit source]

[edit | edit source]

Reference[edit | edit source]

- LONGACRE, T. A. a C. M. FENOGLIO-PREISER. Mixed hyperplastic adenomatous polyps/serrated adenomas. A distinct form of colorectal neoplasia. Am J Surg Pathol [online]. 1990, vol. 14, no. 6, s. 524-37, dostupné také z <https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2186644/>. ISSN 0147-5185.

- ↑ REX, D. K., D. J. AHNEN a J. A. BARON, et al. Serrated lesions of the colorectum: review and recommendations from an expert panel. Am J Gastroenterol [online]. 2012, vol. 107, no. 9, s. 1315-29; quiz 1314, 1330, dostupné také z <https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3629844/?tool=pubmed>. ISSN 1572-0241.

- ↑ SNOVER, D. C.. Update on the serrated pathway to colorectal carcinoma. Hum Pathol. 2011, vol. 42, no. 1, s. 1-10, ISSN 1532-8392.

- ↑ BETTINGTON, M., N. WALKER a A. CLOUSTON, et al. The serrated pathway to colorectal carcinoma: current concepts and challenges. Histopathology. 2013, vol. 62, no. 3, s. 367-86, ISSN 1365-2559.

- BARETTON, G. B., F. AUTSCHBACH a S. BALDUS, et al. Histopathologische Diagnostik und Differenzialdiagnostik serratierter Polypen im Kolorektum. Pathologe. 2011, vol. 32, no. 1, s. 76-82, ISSN 1432-1963.

- ↑ LI, S. C. a L. BURGART. Histopathology of serrated adenoma, its variants, and differentiation from conventional adenomatous and hyperplastic polyps. Arch Pathol Lab Med [online]. 2007, vol. 131, no. 3, s. 440-5, dostupné také z <https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00535-012-0720-y>. ISSN 1543-2165.

- ↑ AUST, D. E. a G. B. BARETTON. Serrated polyps of the colon and rectum (hyperplastic polyps, sessile serrated adenomas, traditional serrated adenomas, and mixed polyps)-proposal for diagnostic criteria. Virchows Arch. 2010, vol. 457, no. 3, s. 291-7, ISSN 1432-2307.

- ↑ BETTINGTON, M., N. WALKER a C. ROSTY, et al. Critical appraisal of the diagnosis of the sessile serrated adenoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2014, vol. 38, no. 2, s. 158-66, ISSN 1532-0979.

- ↑ TORLAKOVIC, E. E., J. D. GOMEZ a D. K. DRIMAN, et al. Sessile serrated adenoma (SSA) vs. traditional serrated adenoma (TSA). Am J Surg Pathol. 2008, vol. 32, no. 1, s. 21-9, ISSN 0147-5185.

- ↑ JASS, J. R.. Classification of colorectal cancer based on correlation of clinical, morphological and molecular features. Histopathology. 2007, vol. 50, no. 1, s. 113-30, ISSN 0309-0167.

- ↑ ROSTY, C., D. G. HEWETT a I. S. BROWN, et al. Serrated polyps of the large intestine: current understanding of diagnosis, pathogenesis, and clinical management. J Gastroenterol [online]. 2013, vol. 48, no. 3, s. 287-302, dostupné také z <https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs00535-012-0720-y>. ISSN 1435-5922.

- ↑ HAQUE, T., K. G. GREENE a S. D. CROCKETT. Serrated neoplasia of the colon: what do we really know?. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2014, vol. 16, no. 4, s. 380, ISSN 1534-312X.

External links[edit | edit source]

- PathologyOutlines.com. Colon tumor > Polyps > Serrated adenoma/polyp [online]. ©2011. [cit. 6/2014]. <http://www.pathologyoutlines.com/topic/colontumorserrated.html>.