Eye and Vision Disorders (Paediatrics)

In young children, the most common eye defects include squint, amblyopia, high farsightedness, nearsightedness and astigmatism. There is an increased risk of eye defects in families where eye defects already occur. The probability that the child will inherit the defect is up to 70%.

A one-year-old child's visual functions are only about 10% developed, a three-year-old child already has 80% of an adult's. The development of sight and spatial vision is practically complete at the age of six to eight.[1]

Eye and vision disorders in children include: pathological position of the bulb (strabismus, nystagmus), decrease in visual functions (especially visual acuity), changes in the front segment of the eye, changes in the background of the eye.

Strabismus[edit | edit source]

Squinting (strabismus) is a condition where one eye follows an object, the other eye turns in the other direction and this could cause double vision. The brain prevents double vision by ceasing to perceive information from the squinting eye, and if this condition persists for a long time, amblyopia from strabismus occurs. Another way the brain copes with this situation is to create pathological cooperation. This means that the eyes learn to work together, but a new point of sharpest vision is created on the retina . But this place physiologically does not correspond to the yellow spot on the retina, and the cooperation of the eyes created is therefore of poor quality.

Up to about 4 (maximum 6) months of age, occasional squinting is considered normal.

Dynamic squinting (concomitant strabismus) is the result of a central disorder in the coordination of the motility of both eyes. Untreated, it leads to amblyopia, loss of spatial vision and cosmetic defect of the affected person.

Strabismus can be convergent (convergent, esotropia) or divergent (divergent, exotropia). It is more common towards the nose. Strabismus is very often associated with a refractive error (strabismus ex anopsia).[1]

Treatment of strabismus:

- Eyeglass correction.

- Orthoptic exercises on special orthoptic devices (eye rehabilitation).

- Surgery (in preschool age, children usually wear glasses even after surgery).[1]

Nystagmus[edit | edit source]

Nystagmus starting before 2 months of age is most likely neurological or congenital. However, it is always necessary to rule out an ocular cause. [1]

Refractive defects[edit | edit source]

Refractive defects (ametropia) arise as a result of a violation of the ratio between the refractive power of the optical apparatus of the eye and its anteroposterior length. They include myopia and hypermetropia; astigmatism and anisometropia (difference in refraction of both eyes). If refractive errors are not caught and corrected in time, they cause amblyopia in children.

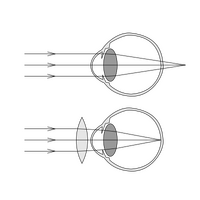

Farsightedness (hypermetropia) is most often caused by the anterior-posterior axis of the eye being shorter than it should be from birth (i.e. axial defect). The light rays are then refracted behind the retina instead of on it. Since the human eye is able to partially compensate for this fact by accommodation, the defect may not be apparent at first. This defect can cause premature fatigue and overaccommodation headaches in children. The child has problems with reading, painting, fine motor skills. It is corrected by spectacle correction with convex lenses, couplings. Some degree of farsightedness occurs in all term infants, but it usually disappears with age. In about 6% of children, farsightedness values remain higher, which can lead to squinting, or amblyopia can subsequently occur.

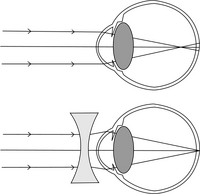

Short-sightedness (myopia) - the disposition to short-sightedness is also congenital. In most cases, myopia does not become apparent until school age, but rarely even earlier, for example in premature children after ROP (retinopathy of prematurity) or CP (cerebral palsy). The cause is most often an eye that is too long , i.e. an axial defect. Another cause may be the greater optical power of the cornea and lens than is necessary for the eye, which leads to light rays converging in front of the retina and creating a blurry image on the retina. It can also be an index defect from refractive errors of optical media (cornea, lens and especially vitreous). It is most often discovered after entering primary school, when the child has problems reading the text on the blackboard. He can see the child up close without any problems. If he squints or closes his eyes outside or while watching TV, we also recommend an eye examination. Myopia is corrected with concave, diverging lenses and should be corrected with the weakest diopter value with which the child can read the required character size monocularly.

Astigmatism – uneven curvature of the cornea (rarely the lens), during which the patient sees poorly both far and near. It can occur alone or with both myopia and hypermetropia. It is corrected with so-called cylindrical glasses.[1]

Diagnosis of refractive errors[edit | edit source]

Examination of visual acuity is part of regular pediatric preventive examinations.

- In newborns, fixation can be examined using an ophthalmoscope.

- In young children, visual acuity can be determined by preferential vision - these are different tests that can capture tracking responses and fixations to movement.

- From the age of 3, visual acuity is examined on picture optotypes , from 4 years on E optotypes , from 7 years on optotypes with letters .

An ophthalmologist always examines refractive errors in cycloplegia, i.e. after applying eye drops (cycloplegics), which not only widen the pupils, but also temporarily disable the ability to accommodate. Automatic refractometers are used to measure refraction. In infants and small children, fluoroscopy is also used, which is based on the evaluation of the disparity of the refractive power of the optical environment and the length of the bulb. The ophthalmologist uses a retinoscope or a flat mirror to elicit a light reflex from the child's fundus. By placing the lenses in the fluoroscopy bar, their hyperopic or myopic value gradually increases. [1]

Treatment of refractive errors[edit | edit source]

- Spectacle correction, for significant refractive defects of contact lenses.

- Laser correction - the corneal epithelium is only partially delaminated from the corneal stroma with a special knife and again after the laser procedure itself

folded back to its original position.

- Continuous monitoring is necessary. [1]

Amblyopia[edit | edit source]

Amblyopia is the inability of the brain to perceive the image coming from the retina. It occurs during the period when both eyes begin to work together through the fusion reflex. During this period or later, if the image coming from one eye is less sharp compared to the other eye, the brain "turns off" that eye so that it is not disturbed by double vision. Amblyopia can accompany eye defects, anisometropia, strabismus, astigmatism, hypermetropia, but the cause can sometimes also be various congenital eye defects, acquired opacities, disorders of the retina or optic nerve. A child with amblyopia may not have any difficulties, it is often discovered accidentally during an eye examination. In amblyopia, the image from the affected eye is perceived less sharply, which is usually the cause of the development of binocular vision (perception of images from each eye in one resulting image).[1]

The basis of successful treatment is its timely initiation. Visual function that is not trained within six to eight years is permanently lost.

Pleoptic treatment - the child is given prescription glasses, the healthy eye is covered with an occluder, and thus the myopic eye is forced to take over the function. Treatment is difficult and unpleasant for children, which is why motivation is important. Treatment with occlusion should be active. He most often uses the cooperation of eye and hand. Therefore, the most suitable exercises are games and puzzles - i.e. for example putting together puzzles, building blocks, looking at pictures, drawing and more. Treatment takes years. Since the treatment of amblyopia affects only one eye, the development of binocular vision can be slowed down or stopped completely. Pleoptic and orthoptic treatments have the task of stimulating the development of binocular vision and strengthening its individual components. [1]

Congenital cataract[edit | edit source]

Congenital cataract , or congenital cataract, disrupts the optical transparency of the lens during a critical period of development of visual functions. Immediately after birth, the visual perception in the affected eye is reduced. The result can be a rapidly developing and later difficult-to-treat amblyopia and a disorder of binocular functions - i.e. functions that enable simultaneous observation with both eyes. Early detection of congenital cataracts is a key moment in therapy, which is why nationwide screening was introduced in maternity hospitals .

Congenital cataract can be bilateral or unilateral, and its causes are diverse. Viral, parasitic or other inflammatory infections in the prenatal period apply here. Furthermore, genetic predispositions (familial) can be at work. However, a number of cases remain unexplained (idiopathic). Cataract symptoms include: a grayish sheen in the pupil, squinting, nystagmus or wandering eye movements.

Therapy: microsurgical removal of the clouded lens and replacement with the application of an intraocular artificial lens, if necessary. correction of the resulting dioptric change with contact lenses or special glasses. Already from 2-3 months of age. Permanent follow-up at a specialized workplace is necessary, where the development of diopters, eye growth, visual acuity are regularly evaluated and all developmental changes are always responded to quickly. The goal is to develop visual acuity and binocular vision as much as possible. [2]

Glaucoma[edit | edit source]

Glaucoma, or congenital glaucoma, is a disease in which, as a result of increased intraocular pressure and other factors, the nerve structures of the retina are damaged, and visual functions are subsequently impaired. The main symptoms of the disease include photophobia, lacrimation, blepharospasm (spasm of the eyelids), graying of the cornea or enlargement of the entire eye (hydrophthalmos) as a result of increasing intraocular pressure, to which the child's eye gives way due to its elasticity and thereby enlarges (parents, paradoxically, have the impression that their child has beautiful big eyes).

Congenital glaucoma is most often caused by a disturbance in the circulation of intraocular fluid in a child's eye. The cause is often the presence of a mechanical obstacle that prevents proper filtration in the iris-cornea angle. There are also genetic predispositions to glaucoma. Congenital glaucoma is more common in boys and in the Roma population. Congenital glaucoma can also be part of other, often rare, congenital defects. It is associated, for example, with Sturge-Weber or Marfan syndrome or neurofibromatosis.

Diagnostics is performed under general anesthesia. Treatment - local antiglaucomatics; intraocular microsurgical operation - so-called drainage, filtering operation with the aim of freeing drainage channels; event laser cyclophotocoagulation - reduction of intraocular fluid production in the ciliary body. Necessary lifelong monitoring (intraocular pressure, visual field, state of nerve fibers on the retina - GDX examination). The prognosis of the disease depends on when glaucoma was diagnosed, its course and treatment.[2]

Retinoblastoma[edit | edit source]

Retinoblastoma (Rb) as a malignant intraocular tumor threatens the patient's life and therefore early diagnosis is particularly urgent. It is a typical tumor of childhood, most often affected are children under 3 years of age, the disease is manifested by squinting due to impaired vision, leukocoria and, in the late stages, eye irritation. With early detection and joint ophthalmological and oncological treatment at a specialized workplace, enucleation of the affected eye can be avoided. Permanent medical care is also necessary due to the increased risk of secondary malignancies in later life.

Retinoblastoma is the most common intraocular tumor of childhood with an incidence of 1 in 14,700–22,600 births[3] ; in the Czech Republic, an average of 6 to 7 children are diagnosed with this disease every year.

Hereditary, bilateral or multifocal retinoblastoma is caused by a germline mutation of the retinoblastoma gene (Rb1) (mostly de novo, less often inherited). This accounts for about 40% of retinoblastomas. It is mostly diagnosed in children around one year of age.

The unilateral form of retinoblastoma creates only one focus, and occurs more often in older children between the 1st and 3rd grade. year of age. The Rb1 gene is mutated only in tumor tissue. 10-15% of children with hereditary retinoblastoma have the disease localized in only one bulb, therefore a genetic examination of peripheral blood is always necessary.

Retinoblastoma grows from the light-sensitive layer of the eye under the retina and into the vitreous space. As the tumor progresses, there is invasion of tumor masses (seeding) into the choroid and/or through the lamina cribrosa into the optic nerve, both of which increase the risk of metastases to the CNS. It can advance per continuitatem into the orbit through the coverings of the eye. Among the rare and very advanced forms of Rb is trilateral retinoblastoma, which affects both eyes and there is also a tumor focus in the brain, in the pineal region.

The most common symptom is leukocoria, a whitish reflex in the pupil that is usually visible in a photo taken with a flash. Another frequent manifestation of retinoblastoma is strabismus, especially if the tumor affects the macular retina. Other symptoms may include orbitocellulitis, iris heterochromia (different color in both eyes) and increased intraocular pressure.

The diagnosis is performed under general anesthesia - indirect ophthalmoscopy with impressions, ultrasonographic examination of the bulbs and orbits, and photo documentation. The diagnosis also includes an MRI of the brain and a genetic examination of the peripheral blood for possible somatic mutations of the Rb1 gene. In advanced Rb, a lumbar puncture or bone marrow aspiration, skeletal scintigraphy, lung X-ray examination and abdominal ultrasonography are added to find potential distant metastases.

Treatment:

- local techniques - enucleation, cryotherapy, transpupillary thermotherapy, brachytherapy, intravitreal or episcleral chemotherapy;

- systemic techniques: systemic chemotherapy or chemotherapy administered selectively to the ophthalmic artery, external radiotherapy (photon or proton).

Retinoblastoma is usually a curable disease in developed countries, if the tumor is present only in the eyeball, the chance of a total cure is almost 100%. [4]

Congenital developmental anomalies of the eye[edit | edit source]

Congenital developmental anomalies represent a larger group of rare disabilities that are usually manifested already in the youngest children and are associated with a significant decrease in visual functions. Iridocorneal dysgenesis, persistence of primary hyperplastic cornea and congenital ptosis are relatively common.

Physiological development of vision[edit | edit source]

- Newborn: scotopic vision (rod-mediated dim vision; used to detect moving non-contrast objects and changes in space) and unidirectional, conjugate, searching eye movements - version;

- 2nd week: onset of photopic vision (seeing a still, high-contrast object under lights and perceiving colors);

- 1st month: monocular peripheral fixation, fixation and gaze reflex;

- 2nd month: binocular peripheral fixation, version;

- 3rd month: central fixation and opposite, disconjugated movements - vergence;

- 4th month: full accommodation, accommodative convergent reflex;

- 6th month: completion of fovea and foveola development, permanent central fixation, beginning of fusion (the brain combines the images of both eyes into one spatial perception);

- 9-12 month: fixation of binocular reflexes (fixation, accommodation-convergence and fusion reflex);

- 3 years: consolidation of the fusion reflex;

- 4-6 years: recognition of spatial vision, consolidation of binocular vision.[1][5][6]

Problems of Neonatal and Infancy[edit | edit source]

Conjunctivitis or problems with the tear ducts (congenital narrowing or obstruction) are typical for newborns and infants, which are manifested by repeated inflammation and tearing, usually in one eye. It is solved either conservatively with drops and digital pressure massage of the lacrimal sac, or with irrigation or probing of the lacrimal ducts.

Newborns can also develop cataracts and glaucoma. Unfortunately, it is also possible to diagnose a malignant tumor of the retina (retinoblastoma) during the first to second year of a child. This cancer can only be treated at a specialized workplace and in cooperation with oncologists. Comprehensive and timely therapy has good results.

Eye defects begin to appear from the 6th month. Farsightedness is the most common, followed by nearsightedness and astigmatism. Amblyopia and squint can only be treated in childhood. If they persist after the sixth and seventh years, they are already permanent, and after the eighth year it is usually not possible to train the eye and involve it in spatial perception.[1]

Eye and Vision Examination[edit | edit source]

Currently, the so-called screening for congenital cataracts is carried out in the maternity hospital for every newborn . By illuminating each eye with an ophthalmoscope, it is determined whether the optical media of the eyes is clear. Early detection and correction has a major impact on the future development of visual functions. Congenital cataracts can be operated on just a few weeks after birth.

The pediatrician performs an eye examination as part of all preventive examinations . Eye defects or deviations are often noticed by parents who are in constant contact with the child. For children who do not cooperate and therefore cannot undergo an optotype examination, it is possible to screen their eyesight using a portable autorefractometeru (Plusoptix), which measures refractive errors, eye position, corneal reflexes, pupil diameters. The child sits on a chair or on the parent's lap. A camera is pointed at him with accompanying light and sound effects to capture his gaze. Infrared light passes through the pupil on the retina, and the reflected light from the retina creates a specific light pattern on the pupil depending on the degree of refractive error. Spherical refraction values are calculated from the character of this figure, the measurement is repeated in three meridians so that possible astigmatism can also be detected. The examination is non-contact, binocular, without the need for eye drops, it is quick, child-friendly and undemanding, completely painless and can be performed from 6 months of age. [1]

Links[edit | edit source]

Related Articles[edit | edit source]

External links[edit | edit source]

https://www.pediatriepropraxi.cz/pdfs/ped/2013/06/03.pdf

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l STROFOVA, H and P TEPLANOVA. Screening for visual defects in children. Pediatrics for Practice [online] . 2014, year 15, vol. 6, pp. 334-336, also available from < https://www.solen.cz/pdfs/ped/2014/06/02.pdf >.

- ↑ a b ODEHNAL, M. Congenital cataract and glaucoma. Sanguis [online] . 2010, year -, vol. 83, p. 85, also available from < http://www.sanquis.cz/index1.php?linkID=art3291 >.

- ↑ MacCarthy A, Draper GJ, Steliarova-Foucher E, Kingston JE. Retinoblastoma incidence and survival in European children (1978–1997). Report from the Automated Childhood Cancer Information System project, Eur J Cancer, 2006; 42: 2092–2102.

- ↑ ŠVOJGR, K. Retinoblastoma. Oncology [online] . 2016, year 10, vol. 5, pp. 215–217, also available from < https://www.solen.cz/pdfs/xon/2016/05/03.pdf >.

- ↑ Krásný J, Autrata R. Pediatric ophthalmology and strabismus. In: Kuchynka P, et al. Ophthalmology. Prague: Grada, 2007: 645–726.

- ↑ Zobanová A. Physiological development of vision in children during the first years of life. Neonatology Letters 1997; 3(4): 292–296.