Active immunisation

It has been known for many millennia that people only very rarely get sick twice with the same infectious disease. For example, in the plague epidemics of the Middle Ages, those caring for the infected did not fall ill. The first attempts at vaccination were made in 1796 by Edward Jenner (an English physician), who noticed that suckling cows exposed to cowpox virus were never infected with variola virus (smallpox). Hence the name vaccination from the Latin word vacca (cow).

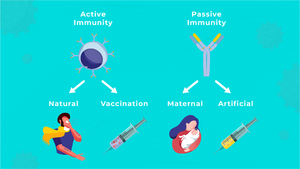

The goal of active immunization is to induce specific immunity against a particular antigen or organism. Active immunity can be divided into:

- post-infectious, which occurs after a natural encounter with the antigen,

- post-vaccination, which is achieved by vaccination (inoculation).

Vaccinations[edit | edit source]

The effectiveness of vaccination can be observed by comparing morbidity and mortality from infectious diseases before and after the introduction of vaccination. The greatest success of vaccination has been the eradication of variola (smallpox). The principle of vaccination is the artificial injection of an antigen into the body to produce its own specific antibodies.

- Vaccines must meet the following criteria

- safety - must not cause disease or harm the body with various additives;

- specificity - it must induce the production of antibodies against the antigen in question (which is present during infection and subsequent disease, and not another);

- presentable antigen - if the antigen is unable to present with MHC II molecules, it would not cause an immune reaction;

- efficacy - the vaccine must be potent enough to induce antibody levels high enough to protect against disease; antibodies should remain in the body for as long as possible (ideally for life, in the IgG class);

- should not cause any serious adverse reactions;

- ease and accuracy of immunisation (i.e. method, injection site, needle, etc.);

- affordability of the vaccine.

Vaccination is meaningful if it is nationwide or target group vaccination. The number of doses of the core vaccination should be reasonable (maximum 4-5 doses). Adherence to the timing schedule and, of course, adequate health status of the vaccinated person are also important. The success of the vaccination itself is determined not only by the effective vaccine, but above all by the good will to have your child vaccinated.

Types of vaccines[edit | edit source]

- Vaccines are divided into

- attenuated (live attenuated) - by passaging on culture media, the bacteria or virus loses its pathogenicity while retaining its antigenic structure (measles, rubella, mumps, polio - Sabin's poliovaccine, anti-tuberculosis BCG vaccine, etc.);

- killed - suspension of killed bacteria (bacterins) or viruses without damaged surface antigens (pertussis, celovirus vaccine against influenza, rabies, hepatitis A);

- toxoids (anatoxins) - bacterial toxins with suppressed toxicity and preserved antigenicity (tetanotoxin, diphtheria and pertussis toxin);

- subunit - viral particles are split and purified, removing toxic parts of the viral antigen reduces reactivity - the advantage is a lower incidence of side effects and pathological reactions to vaccination (influenza);

- Conjugated vaccine (chemo vaccine) - usually a T-independent polysaccharide antigen conjugated to an immunogenic protein. This is because the immune system of young children would not be able to respond to the antigen alone (pneumococcus, meningococcus, Haemophilus influenzae type B).

- recombinant (vector) - a clone of yeast or bacteria produces a large amount of antigen after introducing a gene (hepatitis B, pertussis);

- DNA vaccine - is similar to a recombinant vaccine, except that the carrier is the entire DNA that is introduced into the cell of the vaccinated person; this vaccine is still in the experimental stage;

- synthetic - prepared chemically, expected biological and chemical purity, low price;

- autovaccine - a vaccine prepared from a pathogenic strain cultured from an affected person. It is thus tailored to the specific patient and is not essentially a vaccination, but an immunostimulation. Vaccination against Propionibacterium acnes is being tested for severe acne. It is also expected to be used in chronic infections and carrier disease.

To ensure the safety and efficacy of vaccination, spacing of vaccines is essential:

- after the inactivated vaccine for 2 weeks;

- after the live vaccine for 4 weeks;

- 2 months after tuberculosis vaccination (always after the initial reaction has healed);

- after skin tests, including tuberculin, for 1 week.

Response to vaccination[edit | edit source]

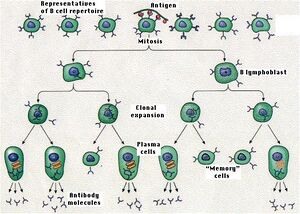

Clonal selection and clonal expansion of lymphocytes occurs upon initial encounter with the antigen. After repeated encounters with the antigen, because of the presence of memory cells, the likelihood of immune cells encountering the antigen is greater and the activation of lymphocytes in this situation is also faster. Therefore, repeated encounters with the antigen accelerate the onset of the immune response as well as its strength.

Reactions after vaccination[edit | edit source]

They may be local, general or unusual.

- Local reactions

- edema,

- redness,

- soreness at the injection site of the vaccine

- Overall reaction

- elevated temperature (above 37 °C subfebrile x 38-41 °C fever),

- headache,

- arthralgia (pain in the joints or muscles),

- mild exanthema with measles vaccine ("mitigated measles" 5-12 days after vaccination; about 5% of those vaccinated).

- Unusual reactions

- abscess at the injection site,

- high temperatures above 38 °C,

- meningeal irritation,

- post-vaccination encephalitis.

An unusual reaction should be reported to the Health Institute and the Institute for Drug Control in Prague and a batch of the vaccine used should be provided for testing.

Physiological reactions include increased temperature, muscle pain, fatigue. They occur in about 10-15% of vaccinees. After administration of inactivated vaccines, reactions occur within 48 hours after administration, after administration of live vaccines usually in 1 week.

Post-vaccination regimen:

- 30 minutes at rest, under medical supervision (rare risk of anaphylaxis);

- then without increased physical exertion - 2 days after inactivated and 2 weeks after live vaccine.

Contraindications to vaccination[edit | edit source]

Contraindications are divided into temporary (acute illness, convalescence, incubation period) and permanent.

Temporary contraindications: acute febrile illness, suspected infection, early convalescence stage (vaccination can be given no earlier than 14 days after the infectious disease has resolved), active tuberculosis.

Clearly permanent contraindications are congenital immunodeficiency or malignant disease (leukemia, etc.), which applies primarily to the administration of live vaccines; anaphylactic type of allergy to one of the components of the vaccine (egg protein - MMR), severe reactions after the first administration of the vaccine.

We individually assess vaccination in people treated with immunosuppressive drugs, including corticosteroids, and in people with active neurological diseases.

Pertussis bacterin is contraindicated in active nervous diseases (epilepsy, infantile spasms, afebrile convulsions, progressive encephalopathy.

Unjustified contraindications are manifestations of atopy, metabolic disorders, including diabetes, stable neurological disease (except for vaccination for pertussis).

Vaccination in the Czech Republic[edit | edit source]

Vaccination in the Czech Republic is governed by Decree 355/2017 Coll.

- There are several types of vaccination

- regular vaccinations - e.g. against diphtheria, tetanus, whooping cough, Haemophilus influenzae type b, polio and viral hepatitis B; measles, mumps and rubella;

- special vaccinations - for people at increased risk of infection, e.g. hepatitis A, hepatitis B, rabies, seasonal influenza;

- emergency vaccination - in emergency situations such as epidemics, pandemics, natural disasters, etc;

- In addition, vaccinations are given for accidents and injuries, when travelling abroad or at the direct request of the patient.

| Regular vaccinations | Age |

|---|---|

| Hexavalent vaccine (diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, Haemophilus influenzae b invasive disease, viral hepatitis B and transmissible polio) | from the 9th week after birth, 4 doses |

| measles, rubella, mumps | from the 15th month, 2 doses |

List of compulsory vaccinations (valid as of 1.1.2018)[edit | edit source]

| Age | Compulsory vaccinations (from 1.11.2010) | Compulsory vaccinations (from 1.1.2018)

Decree 355/2017 Coll. |

Optional/special vaccinations |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4 days - 6 weeks | tuberculosis (only in children at risk with indications) | tuberculosis (only in indicated cases) | |

| 6 weeks | rotavirus (1st dose) | ||

| 2 months | hexavaccine

(1st dose from week 9) |

hexavaccine

(1st dose from 9th week, for children vaccinated against TB - from week 13, always after the reaction has healed) |

Pneumococcus (1st dose)

rotavirus (2nd dose - 1 month apart) meningococcus B (1st dose) meningococcus A, C, W-135 and Y (depending on vaccine type) |

| 3 months | hexavaccine

(2nd dose - 1 month apart) |

Pneumococcus

(2nd dose - 1 month apart) rotavirus (3rd dose - 1 month apart) meningococcus B (2nd dose - 1-2 months apart) | |

| 4 months | hexavaccine

(3rd dose - 1 month apart) |

hexavaccine (2nd dose - 2 months apart) | Pneumococcus

(3rd dose - 1 month apart) meningococcal B (3rd dose - 1-2 months apart) |

| 10 months | hexavaccine

(4th dose - 6 months apart) |

||

| 11–15 months | hexavaccine

(3rd dose between 11 and 13 months) |

Pneumococcus (vaccination)

meningococcal B (booster at 12-23 months) | |

| 15 months | MMR (1st dose) | MMR (1st dose at 13-18 months) | chickenpox (1st dose) |

| 21–25 months | MMR

(2nd dose - 6-10 months apart) |

chickenpox (2nd dose) | |

| 5 years | 1st vaccination: diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis

(1st vaccination) |

diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis

(1st vaccination) MMR (2nd dose) |

|

| 10 years | diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, polio (2nd vaccination) | diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, polio

(2nd vaccination) |

|

| 14 years | tetanus

( in the unvaccinated at 10-11 years) |

girls and boys: papillomavirus

(3 doses) | |

| 20–25 years | tetanus (7th dose) |

Explanation:

- MMR = measles, rubella, mumps;

- hexavaccine = diphtheria (diphtheria), tetanus, pertussis (whooping cough), poliomyelitis, Haemophilus influenzae B, hepatitis B.

WHO vaccination targets[edit | edit source]

- Pre-clinically evaluate new vaccines and new systems for their administration.

- Clinically evaluate vaccines for use in developing countries.

- Accelerate the introduction of newly registered vaccines not yet in use.

- Introduce standardisation and control of the production of biological products.

- Ensure that all vaccines supplied to national immunisation programmes are of adequate quality from manufacture to the time of administration.

- Establish a system to ensure the safety of all immunisations administered in the national immunisation programme.

- Strengthen the immunisation programmes of the most important immunisations so that they are available not only at national but also at district level.

- Eradication fields in all countries of the world.

Links[edit | edit source]

Related articles[edit | edit source]

Used literature[edit | edit source]

- LAW, M a L HANGARTNER. Antibodies against viruses: passive and active immunization. Current Opinion in Immunology. 2008, vol. 20, no. 4, s. 486-492, ISSN 0952-7915.

- FRENKEL, LD a K NIELSEN. Immunization issues for the 21st century. Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology. 2003, vol. 90, no. 6, s. 45-52, ISSN 1081-1206.

- ŠTERZL, Ivan, et al. Základy imunologie pro zubní a všeobecné lékaře. 1. vydání. Praha : Nakladatelství Karolinum, 2005. 207 s. ISBN 80-246-0972-X.

- SMÍŠEK, J. Imunizace a očkovací látky [online]. ©2008. [cit. 2009-12-02]. <http://mikrobiologie.lf3.cuni.cz/mikrobiologie/teozak/imun/imunizace.pdf>.

- PETRÁŠ, M. Význam očkování [online]. ©2007. [cit. 2010-21-04]. <https://www.vakciny.net/principy_ockovani/pr_01.html>.

- LAW, M a L HANGARTNER. Antibodies against viruses: passive and active immunization. Current Opinion in Immunology. 2008, vol. 20, no. 4, s. 486-492, ISSN 0952-7915.

- FRENKEL, LD a K NIELSEN. Immunization issues for the 21st century. Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology. 2003, vol. 90, no. 6, s. 45-52, ISSN 1081-1206.

- ŠTERZL, Ivan, et al. Základy imunologie pro zubní a všeobecné lékaře. 1. vydání. Praha : Nakladatelství Karolinum, 2005. 207 s. ISBN 80-246-0972-X.

- SMÍŠEK, J. Imunizace a očkovací látky [online]. ©2008. [cit. 2009-12-02]. <http://mikrobiologie.lf3.cuni.cz/mikrobiologie/teozak/imun/imunizace.pdf>.

- PETRÁŠ, M. Význam očkování [online]. ©2007. [cit. 2010-21-04]. <https://www.vakciny.net/principy_ockovani/pr_01.html>.