Aspiration of a foreign body

Aspiration of a foreign body is a spontanneous and undesirable entry of a foreign body into the airways during inspiration. According to consistency of the inhaled object, it is possible to distinguish between aspiration of solid substances, liquids, emulsions and gases. The presence of a "foreign", unphysiological substance in the airways leads directly or indirectly to the development of pneumonia, i.e., aspiration pneumonia. The most frequent causes of aspiration pneumonia include aspiration of the contents of the mouth by small children, aspiration of the stomach contents in patients with gastroesophageal reflux (GER), swallowing disorders (interestingly, the act of swallowing involves 5 nerves of the head and 26 muscles), neurological disorders and structural abnormalities (cleft palate, oesophageal artresia,tracheoesophageal fistula including the so-called H–type, malrotation, achalasia).

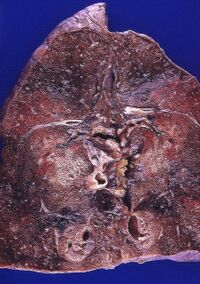

Aspiration causes a complex patophysilogical process. Destructive changes of the pulmonary parenchyme resulting from foreign body aspiration differ from destructive changes caused by infectious agents since they include structural destruction, degenerative (necrotic) changes of the parenchyme and a decrease in dynamic pulmonary compliance with an impaired respiratory function. Therefore, they are sometimes referred to as pneumonititis.

Mechanism of aspiration[edit | edit source]

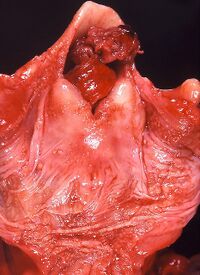

Solitary respiratory tract in the area of HCD appears to be a critical segment in its entirety, but the most serious obstruction is caused by a foreign body lodged in the physiologically most narrow spaces: glottic opening, subglottic region and the carina. The obstruction of HCD may also be caused by external pressure caused by a foreign body lodged in the oesophagus, mainly in the so-called Killian’s dehiscence.

The coordination between swallowing and natural breathing may be disrupted by negative effects, which increase the probability of aspiration and affect various patophysiological levels, i.e. so-called predisposing factors to aspiration:

- impairment of distal esophageal sphincter (GER, inserted nasogastric tube, gastrostomy, hiatal hernia, cardiopulmonary resuscitation, obstruction of upper respiratory tract, mechanical ventilation with negative pressure, muscular dystrophy, scleroderma),

- delayed emptying of the stomach (fear of pain, mechanical intestinal obstruction, peptic gastric ulcer, hypoxia, shock, anaesthesia),

- an increase in intra abdominal pressure or intra gastric pressure (mecanical intestinal obstruction, ascites, abdominal tumor, peritoneal dialysis, VP shunt with fluid drainage, obesity, depolarising myorelaxation),

- disorder of natural defenses of upper respitatory tract (hypoxic–ischemic encephalopathy, traumatic brain injury, encefalitis, meningitis, status epilepticus, anaesthetics, intoxication, incoordination of sucking and swallowing, REM sleep phase),

- anatomic and local factors (vocal cord paralysis, tracheal intubation, tracheostomy, bronchoscopy, lowered laryngeal sensitivity, tracheoesophageal fistula, esophageal diverticulum, mucus accummulation in the pharynx).

Localisation[edit | edit source]

Finding of a foreign body on examination in the larynx is very rare. A smaller foreign body tends to become lodged in the bronchi (usually in the right bronchus, since the right bronchus is less diverted in the bifurcation and it is wider). A large foreign body leads to patienr’s asphyxiation. The presence of foreign bodies in the bronchi is most frequent in toddlers and in pre-school children. These cases mostly involve food substances, most frequently nuts, carrot pieces, soup bones but also beads, small balls, buttons, etc. Foreign object inhalation occurs when a child bursts into laughter or starts crying with his/her mouth full of food. In the alveoli, tiny substances tend to be found, such as ashes, flour, sawdust, sand. [1][2]

Clinical presentation[edit | edit source]

The symptomatology of foreign body aspiration depends on the volume and type of the inhaled material, its pH value, presence of bacteria in the aspirated material and last but not least on the underlying health and immunological profile of the patient before the act of foreign body aspiration. Aspiration has a typical clinical presentation during its initial phase, its progression and development of clinical signs.

The most frequent manifestations of aspiration include recurrent wheezing, apnea, chronic cough and recurrent pneumonia.

Immediately after a foreign body is inhaled, aspiration manifests itself as a coughing attack, which subsides after the foreign body becomes lodged in a specific location. Until that moment, it "travels" between the bronchi and the glottis, and it can be also coughed out. A foreign body wedged in the bronchus usually leads to a creation of a ventil and an emfyzema develops subsequently. When inhaling, the lumen expands and the air circulates behind the foreign body. During inspiration, the bronchi collapse due to foreign body obstruction and are unable to release the air. Inflammation arises around the foreign body, and atelectasis develops.[1]

Initial phase[edit | edit source]

- paroxysmal, irritating and persistent cough (a natural defense mechanism with the aim to expel the aspired body),

- apnea,

- in blood supply of the face and the mucous membranes – blood perfusion, folowed by cyanosis,

- retraction of the chest during inspiration,

- anxiety and psychomotor agitation.

Post-aspiration phase, i.e., signs of acute respiratory distress[edit | edit source]

- mixed dyspnea, stridor and wheezing,

- tachypnea,

- vocal changes,

- cyanosis,

- quantitative disorders of consciousness,

- hemodynamic instability,

- findings during chest auscultation: asymmetry, wheezing, impaired inspirium, impaired breathing and others (up to 40 % of patiens who present with aspiration of an anorganic body have normal physiological findings on examination, unlike patients who present with aspiration of an organic body, out of which only 13 % have normal physiological findings on examination),

- unexplicable night fevers and/or night sweats,

- purpulent sputum,

- night wheezing and/or cough.

Aspiration should be strongly suspected in patients presenting with asthma-like symptomatology, patients irresponsive to standard treatment and patients whose symptomatology is not directly related to the presence of allergens, physical effort or pulmonary infarction. Recurrent pneumonia often affects patients with foreign body aspiration suffering from neorological disorders or patients with recurrent pulmonary microaspirations (e.g., related to GER). Chronic cough (i.e., cough lasting for more than 3 weeks) may be the only symptom of aspiration. After its initial manifestation, aspiration may become oligosymptomatic or even asymptomatic for a period of several hours, days or even weeks until the recurrence of symptoms.

Diagnostics[edit | edit source]

The examination of a patient with suspicion of aspiration aims at its rapid and reliable identification. It is necessary to identify patients with a high risk of aspiration (by means of a detailed and targeted anamnesis, detailed clinical and neurological examination, continuous monitoring of respiratory functions and ECG) as well as continuous monitoring of clinical symptoms. Typical presentation includes breathing through the nose (nasal breathing), besides wheezing, crackles tend to be present, as well as retraction, alternatively grunting and cyanosis. A valuable aspect is evaluation of the dynamics of changes, i.e., blood supply, the quality of cough, respiratory distress, stridor, wheezing, breathing frequency and auscultatory findings. The essential laboratory tests to be performed include arterial blood gas analysis, monitoring of measurement of the arterial oxygen saturation (SaO2), FBC+differential., inflammatory markers (importance is given to the dynamics of changes). Complementary tests include overall IgE (immunoglobulin E) and prick tests; and/or RAST (radioallergosorbent assay testing) if eosinophylic esophagitis or gastritis is suspected, which can show reactions to common food groups.

Chest X-ray[edit | edit source]

Chest X-ray represents a routine diagnostic method. The finding of an emphysema with a mediastinal shift to the opposite side indicates ventil mechanism of an abstruction with a foreign body. The presence of atelectasis with mediastinal shift to the affected side indicates aspiration with a complete obstruction of the bronchus in a a given part of the lungs resulting in resorbtion of the air.

The most frequent X-ray findings include emphysematous changes, followed by the presentation of atelectasis, a normal radiograph, and consolidation. Sensitivity of the X-ray imging techique and its propensity to detect aspiration also depends on the time frame of its implementation. If the X-ray is performed more than 24 hours following aspiration, positive findings tend to be more frequent. On the other hand, it has been shown that if X-raz imaging was performed less than 24 hours following aspiration, up to 30 % of children with a subsequently diagnosed aspiration had a negative (normal) radiological finding when endoscopy was performed. An X-ray image without a finding of aspiration does not exclude the possibility of aspiraton!

Bronchoscopy[edit | edit source]

Diagnostic bronchoscopy performed when a finding of a foreign body is proved also fulfills a therapeutic function. The decision to perform an endoscopy is based on a suggestive anamnesis (paroxysmal coughing), on a positive RTG finding and according to findings of a performed physical examination (differences between the sides of lungs detected during ausculcation). Children younger than 3 years of age tend to have foreign bodies diagnosed much more frequently in the right main bronchus. Up to two thirds of aspirated bodies are represented by nuts of various types. In case of chronic microaspirations, it is instrumental to perform the procedure of bronchoscopy and bronchoalveolar lavage BAL, which reveals the finding of lipophagy. A modern diagnostic method consists in the assay of pepsins during the procedure BAL.

Further examination procedure[edit | edit source]

An ultrasound examination of the digestive tract is performed in order to assess gastric distension, presence of GER, intestinal content and motility and build-up of fluid in the abdomen, i.e., ascites. Native abdominal X-ray performed in a standing position provides information about the content of intenstines, levels of fluid in intestinal lumen, position of nasogastric probe (tube). Bacteriological examination of available samples is performed, including aerobic and anaerobic sputum cultivation, pleural fluid, a blood culture test and gastric aspirate. It is also recommended to perform pulmonary function tests and in specific cases also sweat chloride tests. A barium swallow test may reveal anatomic defects such as a hiatal hernia, malrotation, pyloric stenosis, antral or duodenal algae. All these abnormalities might predispose a patient to GER. Gastro-esophageal scintigraphy, often called “milk scan“, is a radionuclid imaging technique, which may confirm aspiration into the lungs (although its specificity and sesitivity among GER diagnostic procedures is not high). Measuring pH over the course of 24 hours is considered the “gold standard“ of diagnostic procedure for determining the presence of GER. In case of uncertainty, lung inhalation scintigraphy might be helpful, if available. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy with biopsy may reveal infiltration with eosinophilia.

Therapy[edit | edit source]

Pre-hospital procedure[edit | edit source]

In case of witnessing the act aspiration of a foreign body by a child and if the child is conscious, he/she should be encouraged to try to cough out the object. If coughing is not effective and breathing is insufficient or the child loses consciousness, removal of a foreign body should be attempted. Manual removal of a foreign body should never be performed at random or in the hypopharynx since such a procedure may push the foreign object further into the airways. Maintaining a secure airway in an unconscious child should be achieved by holding his/her mandible (lower jaw) and his/her forehead simultaneously while lifting the mandible. If the aspirated foreign body is visible, it needs to be removed!

Maneuvers used to open the airway[edit | edit source]

- Gordon maneuver who are conscious and are breathing spontaneusly:

- An infant is placed head-down on our forearm with his head positioned lower than his body. We hold the infant’s head by his mandibula while supporting our forearm on our thigh. Subsequently, we give the infant five backblows between his shoulderblades. Our free arm is placed on the infant’s back and while the infant is "sandchiwed" between our arms, we flip him/her over (the infant is lying with his back on the forearm). Subsequently, five chest thrusts are carried out similarly as in CPR. The procedure is repeated until the foreign object is expeled or until the infant loses consciousness.

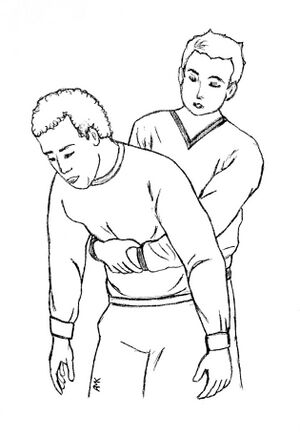

- Heimlich maneuver for older children, who are conscious and are breathing spontaneusly:

- Standing behind the chid, we wrap our arms around the child. We form a "fist" with our hands and put it on the child’s’s stomach between the navel and a processus xiphoideus. Subsequently, the child’s stomach is pressed five times rapidly in and up. We do not press processus xiphoideus in order to avoid internal injuries.

- If the child is unconscious, the same procedure applies to all age groups :

- We place the child on his/her back, while attempting to free his airways. If a foreign body is visible, we have to remove it. If a foreign body is not visible, we start performing artificial breathing. If the child’s chest is rising, we continue until the arrival of EMS (emergency medical services). If the infant’s chest is not rising, the whole procedure including Gordon/ Heimlich maneuver should be repeated.

Performing the Heimlich maneuver on YouTube (english)

Hospital procedure[edit | edit source]

In case of an acute case of aspiration, it is recommended to perform the procedure in steps according to seriousness and dynamics of the development of the clinical symptoms of aspiration. The patient should beunder surveillance for at least 48 hours.

Drainage of the nasopharynx,

should be performed, feeding through the mouth should be carried out and a thin nasogastric tube should be inserted. An adequate oxygenoteraphy, should be provided, and if necessary, intubation with subsequent Artificial pulmonary ventilation should be provided. An intravenous line is applied and liquids are administered according to the calculated daily need of the patient. Wheezing may be relieved by means of Beta-2 mimetics administered by inhalation. Rigid bronchoscopy should be performed in order to extract particles and it may be complemented by BAL. Antibiotics are not indicated across the board but rather in case of fever, deterioration of clinical symptoms, increase of inflammatory markers or an X-ray correlation of aspiration. If antibiotics are indicated, they should be administered mainly intravenously and in the highest recommended dose. Aspiration pneumonia should be treated with 2nd-generation or 3rd-generation cefalosporins, which will cover both gram-positive microflora in the oropharynx and gram-negative bacteria from the gastrointestinal tract. The presence of anaerobic bacterial flora should be expected as well, in which case treatment with the antibiotics lincosamides (clindamycin), is recommended. However, anaerobic coverage is not universally necessary in the initial (empirical) treatment. If the patient’s condition does not improve within 48 hours, broad spectrum. Antibiotics should be administered. The effectiveness of corticoids has not been proved by clinical studies.

Prevention[edit | edit source]

Prevention consists in identifying high-risk patients. In case of vomiting, the patient should be placed on his right side with his chest elevated and with draining of his nasopharynx. In case of gastronasophageal reflux (GER), the trunk should be elevated and if appropriate, prokinetics may be administered. In patients with impaired defense reflexes of the airways, the lowest possible dose of sedatives and anaesthetics should be administered. In case of total absence of defense reflexes of the airways, tracheal intubation should be performed. In order to administer enteral nutrition, thin and soft nasogastric or nasojejunal tubes should be used.

References[edit | edit source]

Related articles[edit | edit source]

External references[edit | edit source]

Reference[edit | edit source]

- ↑ a b BENEŠ, Jiří. Studijní materiály [online]. ©2007. [cit. 14. 12. 2011]. <http://jirben2.chytrak.cz/materialy/orl_jb.doc>.

- ↑ ŠTEFAN, Jiří – HLADÍK, Jiří, et al. Soudní lékařství a jeho moderní trendy. 1. edition. Praha : Grada, 2012. ISBN 978-80-247-3594-8.

Source[edit | edit source]

- HAVRÁNEK, Jiří: Aspirace cizího tělesa.