Gastrointestinal stromal tumor/PGS

Gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST, sometimes the form GISTom is also used, MKN-O: 8936/0 ) is a mesenchymal tumor of the wall of the digestive system. Originally, these were mesenchymal tumors showing neither the character of leiomyomas nor schwannomas, now GISTs include most mesenchymal tumors of the digestive system, e.g. the terms leiomyoma and leiomyosarcoma are intended only for such tumors that have convincing histological and immunochemical features of smooth muscle. The ultrastructure of GISTs contains elements of autonomic nervous system cells (Cajal cells) and smooth muscle, therefore it is assumed that they arise either directly from Cajal cells or from a common precursor of Cajal and smooth muscle cells. The biological behavior can be both benign and malignant, so GISTs are often said to exhibit a spectrum of behavior from benign to malignant. Biological behavior can be predicted mainly by size and mitotic activity. GISTs tend to appear at an older age, the documented difference between the affected sexes is not large. Malignant GISTs are not common tumors. For example, GISTs are most often found in the stomach, while malignant GIST of the stomach represents approximately 2% of gastric malignancies in terms of frequency .

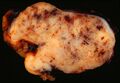

Macroscopic appearance[edit | edit source]

GISTs can be found in any part of the digestive tract, in the omentum and in the mesentery, case reports describing the appearance of a tumor with GIST features in other locations are exceptional. The most common places of occurrence are:

- stomach: 60-70% of cases

- small intestine: 20-30% of cases

- esophagus and colon: together less than 10% of cases

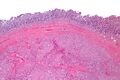

Small GISTs usually present as subserosal, submucosal, or intramural nodules. They are not encapsulated, but they are often well separated from the surroundings. Large GISTs disappear, their surface in the lumen is covered by an intact mucosa, which may, however, be exulsed in 20-30% of cases. The appearance of the tumor may be lobulated. The tumor can directly spread to surrounding organs, for example the pancreas or liver, and infiltrate their parenchyma. The consistency of the tumor can be hard or soft, it is usually light brown on section, there are frequent foci of intraparenchymal hemorrhage. Massive foci of hemorrhagic necrosis and the presence of cystic formations are not uncommon in larger tumors. Multiple occurrence is possible, usually a sign of malignant biological behavior.

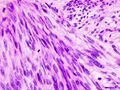

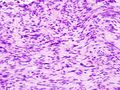

Microscopic appearance[edit | edit source]

Two extremes in the dominant histological picture of GISTs are described. Most GISTs are spindle cell, a smaller part of them is formed by epithelioid cells. These cells can be arranged in a series of patterns. For example, for GISTs of the stomach, eight characteristic patterns can be defined (see GISTs of the stomach ), into which most GISTs can be classified and, according to the group, biological behavior can also be inferred. In contrast, such a classification is not very useful for GISTs of the small intestine.

Both spindle and epithelioid cells can be arranged in the following patterns::

- fascicular arrangement

- storiform arrangement

- palisade arrangement of nuclei to schwannoma -like character

- alveolar arrangement

- formation of organoid structures

The fibrous matrix of GISTs may become hyalinized or myxoid.

The following features are often seen in GIS and may be diagnostically helpful:

- varying degrees of perinuclear vacuolation

- skeinoid fibers – eosinophilic and PAS positive globular masses; if Masson's trichrome is used , they are highlighted by it as well.

- nuclear pleomorphism appears more in epithelioid GISTs, but is usually not very pronounced

- perivascular hyalinization

Conspicuous nuclear pleomorphism is unusual for GISTs.

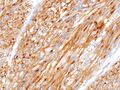

Immunochemical properties[edit | edit source]

- KIT – Membrane tyrosine kinase, its expression is considered by some authors to be defining for GISTs, even though KIT-negative GISTs have been described. Strong positivity is usual, but the staining pattern may vary. The staining pattern does not have to be constant throughout the preparation, in some areas there may even be a loss of stainability. Although KIT is a membrane protein, the entire cytoplasm may be positive.

- PDGFRA – α type of receptor for growth factor PDGF . The PDGFRA mutation is quite common, therefore the positivity is quite sensitive. PDGFRA is also expressed in the intra-abdominal desmoid.

- PKC θ - Protein kinase C θ is a serine/threonine kinase. The sensitivity is relatively high, more so in GISTs outside the stomach. It is not expressed in fibroids and leiomyomas, it is only rarely expressed in schwannomas.

- CD34 – Adhesive protein of hematopoietic and also neural cells. It is demonstrated in 70-80% of cases, the proportion is higher in GISTs of the stomach, on the other hand, only approximately half of the tumors in the small intestine are positive. Due to relatively low sensitivity and specificity, it has limited use in the diagnosis of GISTs.

- DOG-1 – Chloride channel, which is also expressed in KIT-negative GISTs, is highly sensitive and specific.

- smooth muscle markers – About a fifth of gastric GISTs and a third of small intestinal GISTs stain for smooth muscle actin . The positivity of desmin staining is rather exceptional. h-caldesmon positivity is relatively common

- S100 protein – Used more in the differential diagnosis of melanomas and schwannomas. Literární údaje o pozitivity GISTů se pohybují od výjimečné Literature data on GIST positivity range from exceptional positivity to 10% of cases.

- keratins – Sometimes there is a positive reaction with keratin 18, less often with keratin 8. The positivity of other keratins was not observed.

Recommended procedure for histological examination[edit | edit source]

Sample description[edit | edit source]

Partial biopsy[edit | edit source]

- Macroscopic description

- sample type

- ample dimensions (at least the largest dimension)

- Microscopic description

- tumor dimensions (at least the largest dimension)

- location of the tumor (if it can be determined

- morphological subtype (spindle cell, epithelioid, mixed,...)

- mitotic index (if determinable)

- the presence of necrosis

- tumor grade (if it can be determined)

Resection[edit | edit source]

- Macroscopic description

1. type of resection 2. resection dimensions 3. localization of the tumor 4. tumor size (at least the largest dimension) 5. relation to resection margins 6. distribution (unifocal vs. multifocal) 7. mucosal ulceration 8. ingrowth to the peritoneum 9. description of the cut surface (bleeding, necrosis, degenerative changes,...

- Microscopic description

- morphological subtype (spindle cell, epithelioid, mixed,...)

- mitotic index

- the presence of necrosis

- tumor grade

- risk of aggressive behavior

- resection margins

- stage according to pTNM

- for already treated tumors, description of changes associated with therapy (optional)

Further examination[edit | edit source]

Immunochemical examination[edit | edit source]

If the tumor is not smaller than 1 cm and without captured mitoses, the diagnosis should always be verified histochemically, the following three markers are mandatory: KIT, S100 and desmin. These markers will help distinguish between GIST, schwannoma and leiomyoma/leiomyosarcoma:

| KIT | S100 | desmin | pozn. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| leiomyoma/leiomyosarcoma | - | - | + | |

| schwannoma - | + | - | ||

| melanoma | + | + | - | 2. histochem examination of HMB45, melanA |

If staining for KIT, S100 and desmin is negative, the recommended algorithm is as follows:

- Inflammatory appearance of the tumor? If so, then:

- immunohistochemically ALK+, desmin +/-, systemic symptoms: inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor

- intimate contact of spindle cells with lymphocytes, CD21+, CD35+: follicular dendritic cell tumor

- submucosa, presence of eosinophils, cocentric formations, CD34+, PDGFRA mutation: Vaňk's tumor (inflammatory fibroid polyp)

- The vessels have the appearance of endometrium? If so, then:

- CD10+, estrogen receptors+, positive gynecological history endometrial stromal sarcoma

- Staining for cytokeratins? If so, then:

- extensive sampling: sarcomatoid carcinoma

- None of the above?

- second reading, KIT/PDGFRA mutational analysis: solitary fibrous tumor

Molecular genetic examination[edit | edit source]

Molecular biology confirms the diagnosis, the result has a predictive value of the expected response to therapy. It is especially important for metastatic and high-risk tumors.

- KIT gene exon 11 mutation: best response to imatinib therapy

- KIT gene exon 9 mutation: longer progression-free survival with imatinib dose increase, sumatinib benefit

- Asp842Val mutation of PDGFRA gene exon 18: resistance to imatinib

Clinical Behavior[edit | edit source]

Clinical manifestations depend on the size of the tumor and its location. The smallest tumors are usually completely asymptomatic and are incidental findings. Clinically manifest tumors are most often the cause of bleeding into the alimentary canal of varying intensity, or indeterminate manifestations in the abdomen. A less common manifestation is wall obstruction or perforation. Palpable flesh is rather an exception..

Metastatic spread[edit | edit source]

Malignant GISTs can establish distant metastases. It most often spreads to the liver and soft tissues in the abdominal cavity. Metastases to bones and peripheral soft tissues are less common. Metastases to the lymph nodes or the lungs are very rare.

In aggressively behaving GISTs, potential metastases most often appear 1-2 years after resection of the primary tumor. A GIST that does not behave aggressively can also be a source of metastases. These then appear 5-15 years after resection of the primary lesion.

Forecast[edit | edit source]

Biological behavior can be determined primarily by tumor size and mitotic activity. GISTs that are less than 5 cm in diameter are usually benign. Other significant prognostic factors are mitotic activity as well as histological type. The role of the prognostic factor is probably played by the location, e.g. GIST of the stomach generally has a better prognosis than the same size GIST of the same type and with the same mitotic activity in the small intestine..

| size | mitotic activity¹ | stomach | jejunum a ileum | duodenum | rectum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| under 2 cm | low | none | none | none | none |

| 2–5 cm | low | very small | small | small | small |

| 5–10 cm | low | small | high | high² | high² |

| over 10 cm | low | medium | high | high² | high² |

| under 2 cm | high | none | none | high;³ | high |

| 2–5 cm | high | medium | high | high | high |

| 5–10 cm | high | high | high | highsup2; | high² |

| over 10 cm | high | high | high | high² | high² |

- ¹ low mitotic activity here means no more than 5 mitoses per 50 fields of view at the highest magnification, i.e. a mitotic index of no more than 5

- ² small number of cases, the statistical value is not very reliable

- ³ very few or no cases

Other prognostic markers worsening the prognosis are:

- increased Ki67 expression – high proliferative activity

- loss of p16 expression

- multiple occurrence

- infiltrative growth

- the presence of necrosis

- ulceration over the tumor

Prognostically favorable factors are:

- presence of skeinoid fibers (small intestine only)

- nuclear palisade

Of the molecular biological markers, mutational analysis of the KIT and PDGFRA genes appears to be useful

Grading[edit | edit source]

Grading of GISTs is determined exclusively according to the mitotic index. There are only two grades:

- G1 – no more than 5 mitoses/mm²

- G3 – more than 5 mitoses/mm²

Staging[edit | edit source]

TNM staging[edit | edit source]

| Gastrointestinal stromal tumor/PGS | |

|---|---|

| Primary tumor size | |

| TX | the primary tumor was not evaluated |

| T0 | there is no evidence for the existence of a primary tumor |

| T1 | tumor diameter no more than 2 cm |

| T2 | tumor diameter more than 2 cm, maximum 5 cm |

| T3 | tumor diameter more than 5 cm, maximum 10 cm |

| T4 | tumor diameter more than 10 cm |

| Involvement of the lymph nodes | |

| NX | regional lymph nodes were not evaluated |

| N0 | not proof of spread |

| N1 | spread to regional lymph nodes |

| Distant metastases | |

| M0 | they are not |

| M1 | they are |

Clinical stages[edit | edit source]

Clinical stages according to the 7th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer: Cancer Staging Manual (2010) :

| stage | T | N | M | mitotic index |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| stage IA | T1 or T2 | N0 | M | low |

| stage IB | T3 | N0 | M0 | low |

| stage II | T1 | N0 | M0 | high |

| stage II | T2 | N0 | M0 | high |

| stage II | T4 | N0 | M0 | high |

| stage IIIA | T3 | N0 | M0 | high |

| stage IIIB | T4 | N0 | M0 | high |

| stage IV | any T | N1 | M0 | arbitrary |

| stage IV | any T | any N | M1 | arbitrary |

| stage | T | N | M | mitotický index |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| stage I | T1 or T2 | N0 | M0 | low |

| stage II | T3 | N0 | M0 | low |

| stage IIIA | T1 | N0 | M0 | high |

| stage IIIA | T4 | N0 | M0 | high |

| stage IIIB | T2 | N0 | M0 | high |

| stage IIIB | T3 | N0 | M0 | high |

| stage IIIB | T4 | N0 | M0 | high |

| stage IV | any T | N1 | M0 | arbitrary |

| stage IV | any T | any N | M1 | arbitrary |

Behavior in individual bodies[edit | edit source]

Esophageal GIST[edit | edit source]

GISTs are rare in the esophagus, accounting for only about 1-2% of all GISTs. They are 3 times less common than leiomyomas y. They appear more often in the lower third of the esophagus in older patients. Larger GISTs may present clinically with dysphagia, but growth into the mediastinum without swallowing disorders has also been described. The histological picture is more often spindle cell. Few cases have been described to evaluate the long-term prognosis, but the prognosis seems rather poor..

Gastric GIST[edit | edit source]

Gastric GISTs account for about 60% of all GISTs. They occur at an older age, only about 10% of cases occur in patients under 40 years of age. About a fifth to a quarter of all gastric GISTs behave malignantly.

The described size of GIST varies from a few millimeters to more than 40 cm, most often around 6 cm. Malignant GISTs can be associated with surrounding organs.

8 histological types of gastric GIST can be defined, but only 70% of tumors can be classified into them:.

Lze definovat 8 histologických typů GISTu žaludku, do kterých však lze klasifikovat pouze 70 % nádorů:

- sclerosing spindle cell GIST – ousually small, with low mitotic activity, abundant collagenous stroma, calcified in places.

- palisading-vacuolized spindle cell GIST – palisading of the nuclei reminiscent of schwannoma structures is visible, another characteristic feature is a perinuclear vacuole. They are usually larger tumors with low mitotic activity.

- hypercellular spindle cell GIST – dense clustering of uniform spindle cells without distinct nuclear palisading. Mitotic activity is usually not pronounced, but sometimes it is slightly higher.

- sarcomatous spindle cell GIST – jsignificant mitotic activity is evident, diffuse atypia manifested primarily by nuclear hyperchromasia, their enlargement and possibly nuclear pleomorphism. Sometimes a myxoid stroma is formed, in which bands of tumor cells can be observed.

- sclerosing epithelioid GIST – the tumor cells are polygonal, they look like syncytia, cell boundaries are not visible, the stroma is sclerosing. Nuclear atypia is relatively common. Mitotic activity is rather low.

- dyscohesive epithelioid GIST – epithelioid cells are sharply demarcated, lacunar clearing is visible around the cells. Nuclear pleomorphism is common.

- hypercellular epithelioid GIST – cells have well-defined boundaries, are tightly packed, mitotic activity is low.

- sarcomatous epithelioid GIST – cells have an epithelioid morphology, their mitotic activity is pronounced.

In addition to size and mitotic activity, histological type is also an important prognostic marker. Roughly (for details see Miettinen and Lasota, 2006) the risk of metastatic spread is as follows:

- low risk: sclerosing spindle GIST, palisade-vacuolated spindle GIST, and sclerosing epithelioid GIST

- intermediate risk: hypercellular spindle cell GIST, dyscohesive epithelioid GIST, and hypercellular epithelioid GIST

- high risk: sarcomatous spindle cell GIST, sarcomatous epithelioid GIST

Duodenal GIST[edit | edit source]

About 4-5% of all GISTs occur in the duodenum. The tumor can expand into the pancreas and thus clinically and macroscopically mimic a tumor of this location. Spindle cell tumors are more common, about half contain skeinoid fibers (globular PAS positive masses). In roughly a fifth of cases, extensive vascularization occurs, so the tumor resembles a hemangioma. The prognosis of small tumors with low mitotic activity is excellent, while tumors larger than 5 cm in diameter or with high mitotic activity are characterized by high mortality

GIST of the small intestine[edit | edit source]

About 30% of all GISTs occur in the jejunum and ileum, but they represent a higher proportion of malignant GISTs. Overall mortality is 40-50%. They occur more often in elderly patients with a slight predominance of men. Unlike GISTs of the stomach, GISTs of the small intestine do not form clearly distinguishable histological types. The cells are most often spindle-shaped, they can also be epithelioid. The sarcomatous appearance is relatively rare

GIST of the colon and appendix[edit | edit source]

GISTs of the colon and appendix account for about 1-2% of all GISTs. They are more common in older people, and are more common on the right. In the literature, invasion into the muscularis propria is mentioned as a prognostic marker, but other authors question its significance. Furthermore, relatively frequent (up to 25 % of cases) KIT negativity is mentioned; it is added that these are most likely not GISTs but true sarcomas .

Rectal GIST[edit | edit source]

Rectal GISTs account for about 4% of all GISTs. They include both small incidentalomas and large sarcomatous tumors. When growing into the prostate, they can appear as a primary prostate tumor. The histological structure of GISTs of the rectum often contains hyalinized calcifying stroma or a palisade arrangement, but only with a faint perinuclear vacuole. Malignant GISTs may have a fascicular structure similar to leiomyosarcoma. The epithelioid variant is rare here. Skeinoid fibers are usually absent. Clinically, they may appear indolent unless they are the cause of obstruction or bleeding..

GIST outside of GIT[edit | edit source]

Outside the GIT, i.e. more precisely outside the alimentary canal, primary GISTs appear only relatively rarely. They most often appear in the omentum, in the mesentery and in the retroperitoneum. Only a few case reports describe GIST of the gallbladder, larynx, and bladder.

Since metastatic spread is much more likely than the primary formation of GIST outside the alimentary canal, it is debated how much it is, especially in the case of extremely unusual locations, really a primary tumor and how much it is a metastasis from an overlooked primary focus

Differential diagnosis[edit | edit source]

KIT negative GIST[edit | edit source]

Immunohistochemically determined KIT negativity can occur in 2% of small intestinal GISTs and in 5–10% of gastric GISTs. With small biopsy specimens, negativity is more common because there is a higher risk that only a non-histochemically staining area will be included in the biopsy In this case, the diagnosis is based on the histological structure, it can be confirmed by KIT and PDGFRA mutational analysis .

Leiomyoma[edit | edit source]

Leiomyomasy occur less frequently, the ratio to GISTs is 3:1, in the stomach and small intestine their frequency is even lower. Leiomyomas are usually less cellular, their cells are well differentiated, eosinophilic, immunohistochemically they stain for actin and myosin. They can be infiltrated by mast cells y, that express KIT on their surface .

Leiomyomas of the intestinal wall usually present as small sessile polyps. In women, leiomyomas of the uterine type can appear in the abdominal cavity, with no apparent connection to the intestine. These also express receptors for estrogens and progesterone.

Leiomyomatosis peritonealis disseminata is formed by myomas with low mitotic activity, with good differentiation and with immunochemical properties of uterine myomas..

Leiomyosarcoma[edit | edit source]

Primary leiomyosarcoma is rare in the alimentary canal, they occur more often in the large intestine. Leiomyosarcomas are made up of well-differentiated smooth muscle cells with a typical cigarette-shaped nucleus. Retroperitoneal leiomyosarcomas are mostly spindle cell, while retroperitoneal GISTs are more likely to be made up of epithelioid cells Immunohistochemically, actin, obvykle i desmin. KIT is mostly negative, only occasionally focal cytoplasmic positivity can be detected.

Glomus tumor[edit | edit source]

Glomus tumor (glomangioma) is an uncommon benign tumor arising from arteriovenous shunts, glomus bodies. It is usually peripheral, occurrence in the gastrointestinal tract is not usual. Epithelioid GISTs may occasionally be arranged in nests, sometimes arranged around prominent dilated vessels. In this way, they may resemble the histology of a glomus tumor.

Glomus tumor is immunochemically positive when stained for smooth muscle actin kolagen IV and laminin are detected pericellularly . On the contrary, KIT, desmin a S100 protein are not demonstrable CD.is demonstrable in about a third of cases .

Intra-abdominal desmoid[edit | edit source]

Intra-abdominal desmoid (mesenteric fibromatosis) is a tumor-like fibromatous process occurring more often in younger and middle-aged adults. Histologically, it consists of spindle-shaped to star-shaped fibroblasts scattered in an abundant collagenous stroma with slightly dilated blood vessels. Desmoid does not expreses KIT, the previously occasionally reported positivity is now considered more of a false positivity of low-quality antibodies. CD34 34 is negative. Focal positivity in staining for actin and desmin may occur . Detection of nuclear β-catenin can be performed in most desmoids, cytoplasmic positivity can also appear in GISTs.

Inflammatory fibroid polyp[edit | edit source]

Inflammatory fibroid polyp is a submucosal fibroblastic inflammatory lesion, it most often occurs as an ulcerated polyp of the small intestine, rather in younger people. The histological picture can be from a relatively wide spectrum of changes, it can even imitate GIST. Sometimes CD34 can be demonstrated, KIT can never be semonstrated.

Sclerosing mesenteritis[edit | edit source]

Sclerosing mesenteritis is a non-cancerous condition affecting the mesentery of the small intestine Relatively marked inflammatory infiltration and KITnegativity can be used for differentiation .

Solitary fibrous tumor and hemangiopericytoma[edit | edit source]

Solitary fibrous tumor and hemangiopericytom have a number of common morphological features, they are often considered to be variants of the same clinical entity. They are almost always positive for CD34 and negative for aktin and desmin. and desmin. The mast cells present tend to be KIT positive, mostly perivascularly.

Angiosarcoma[edit | edit source]

Angiosarcoma jis rare in the digestive tract. Angiosarcoma can be epithelioid or spindle cell, its cells form true vascular structures The expression of KIT, is usual , to distinguish it from GIST, angiosarcoma markers such as CD31 and von Willebrand's factor must be used (in the pathological literature it is referred to as Factor VIII related antigen ).

Synovial sarcoma[edit | edit source]

Synovial sarcoma can rarely occur in the esophagus, stomach, abdominal wall, and retroperitoneum. KIT may not be positive, some studies describe biphasic KIT positivity, i.e. weak spindle cell positivity and strong epithelial component positivity.

Undifferentiated sarcoma[edit | edit source]

Undifferentiated sarcoma may be macroscopically similar to GIST, but histology shows much greater pleomorphism and much higher mitotic activity than is typical of GISTs. Both KIT and CD34 are usually negative.

Dedifferentiated liposarcoma[edit | edit source]

Dedifferentiated liposarcoma may clinically and macroscopically resemble GIST. If lipomatous foci are not present, more pronounced pleomorphism and more visible fibrous stroma can serve to differentiate it from GIST. Sometimes, individual cells may be positive when staining for KIT.

Gastrointestinal schwannoma[edit | edit source]

Schwannomasare rare in the alimentary canal, and if they do appear, they are more likely to occur in the stomach or large intestine. They are usually small spindle cell tumors with low mitotic activity. They are often surrounded by lymphatic tissue, in which germinal centers can also appear. They tend to be positive when stained for S100 protein and GFAP, they never stain for KIT and CD34.

Gangliocytic paraganglioma[edit | edit source]

Gangliocytic paraganglioma is a mostly benign rare tumor, most often found in the duodenum around the ampulla. It is made up of carcinoid-like elements that are surrounded by schwannoma-like cells mixed with ganglion cells. Unfortunately, even duodenal GISTs tend to have a nested appearance histologically. They tend to be positive for markers of neuronal tissue, often they can also be positive for KIT.

Metastatic melanoma[edit | edit source]

Amelanotic malignant melanoma can metastasize to any part of the colon. Due to the richness of the histological patterns, it may raise the suspicion of GIST. However, melanoma is practically always positive inS100 staining . Melanomas also express KIT, but especially metastases tend to express this protein less.

Epithelioid cell perivascular tumor[edit | edit source]

A perivascular tumor from epithelioid cells is a tumor from the group of angiomyolipomas. It expresses the melanocyte markers HMB45, melan A and MITF, usually does not express S100 and only sometimes expresses smooth muscle markers. Usually KIT is negative.

Histiocytic sarcoma[edit | edit source]

Histiocytic sarcoma is a rare, aggressive tumor. It can cause differential diagnostic difficulties in relation to pleomorphic GISTs. ExpressesCD163, CD6], lysozyme and often S100. Expression of markers of epithelium, lymphatic cells, dendritic cells and melanocytes is usually not demonstrable.

Extramedullary myeloid tumor[edit | edit source]

Extramedullary myeloid tumor ((myeloid sarcoma, chloroma) is a lesion formed by primitive myeloid cells. It often accompanies one of the forms of leukemia . It is usually positive in staining for KIT and CD34, ovšem exprimuje i markery myeloidní řady jako je LCA, CD43, mbut it also expresses markers of the myeloid lineage such as LCA, CD43, myeloperoxidase or lysozyme

Mastocytoma[edit | edit source]

Mastocytoma can very rarely manifest as a solitary tumor mass without other characteristic accompanying manifestations. Staining for KIT is usually positive on cell membranes. It also expresses chloroacetate esterase, tryptase, CD45, CD68 and CD33.

Seminoma and ovarian dysgerminoma[edit | edit source]

Seminoma and ovarian dysgerminoma can be a source of diagnostic embarrassment if they occur in a retroperitoneal location. In addition to the significantly different histology, their positivity for PLAP and OCT4 can be a diagnostic clue.

Cancer metastases[edit | edit source]

Metastases of some cancers can also be a source of diagnostic embarrassment, especially due to frequent positivity in KIT staining

Therapy[edit | edit source]

The basic therapeutic procedure is tumor resection with evidence of intact resection margins. Because GISTs rarely metastasize to the lymph nodes, their biopsy or removal is irrelevant.

GISTs are resistant to conventional chemotherapy, trials with doxorubicin and ifosfamide, i.e. cytostatics used in sarcoma therapy, ended in failure. Similarly, GISTs are also resistant to radiotherapy.

A key event in the pathogenesis of approximately 80% of GISTs is the mutation of KIT, a transmembrane tyrosine kinase that serves as a receptor for the cytokine SCF (Stem Cell Factor). Inhibition of this kinase with the tyrosine kinase inhibito imatinibrepresents a non-surgical approach that has a certain therapeutic effect. The first patient with metastatic and surgically intractable spread of GIST was treated in Finland at the turn of the century with a noticeable remission of the disease, including demonstrable regression of already existing metastases. However, in a minority of patients treated with imatinib, further progression of the disease already occurs during therapy or only growth arrest, but in the majority there is more or less regression, although complete disappearance is not usual. Imatinib is used in the therapy of unresectable and metastatic GISTs.

Molecular pathology[edit | edit source]

The key mutation in the pathogenesis of GISTs is not just one. The most common mutation is KIT, i.e. the receptor for the cytokine SCF (Stem Cell Factor). A mutation of this gene is demonstrable in approximately 80% of cases. The second most common mutation is the mutation of PDGFRA, i.e. the alpha receptor for the cytokine PDGF (Plated Derived Growth Factor). Plated Derived Growth Factor). This mutation is detectable in approximately 10% of cases. Since in both cases it is a receptor with tyrosine kinase activity, GISTs are sensitive to imatinib. in both cases . Both receptors are from family III receptors with tyrosine kinase activity, they further transmit the signal by phosphorylating proteins from the MAPK, PI3K and p90RSK signaling cascades. In both cases, the mutation leads to permanent activation of the receptor.

Syndromes with both KIT and PDGFRA mutations in germline cells have been described. Penetration of GISTs is practically 100% in these syndromes. Hyperplasia of Cajal cells is common. KIT mutation further manifests as urticaria pigmentosa and skin hyperpigmentation.

The remaining roughly 10% of tumors do not have a mutation in any of the above genes. Tumors without mutations in the KIT and PDGFRA genes are referred to as wild-type phenotype.

GISTs with a KIT mutation[edit | edit source]

The KIT mutation was described in GISTs in 1998. KIT is a transmembrane receptor that passes through the cell membrane once. Ligand binding (SCF) will enable the close approach of two monomers, their binding and autophosphorylation of intracellular domains. The receptor activated by autophosphorylation further activates the signaling cascade proteins MAPK, PI3K and p90RSK.

The distribution of mutations is not uniform along the entire gene

- mutation in exon 11: 65–70% of cases (i.e. all GISTs)

- mutation in exon 9: 10–15% of cases

- mutation in exon 13: 1.2% of cases

- mutation in exon 17: 0.6% of cases

- mutation in exon 8: 0.2% of cases (only a few case reports)

Exon 11 encodes the region of the receptor located close to the cell membrane from the intracellular side. Mutations in exon 11 allow the receptor to adopt a conformation leading to activation even without ligand binding. Deletions, insertions and substitutions occur, deletions are associated with a worse prognosis compared to other mutations in exon 11.

Exon 9 encodes a region adjacent to the cell membrane from the extracellular side. Biologically, it is a region supporting receptor dimerization, which is one of the activation steps. Exon 9 mutation is associated with lower sensitivity of GIST to imatinib. Mutations in exon 9 occur more frequently in GISTs of the small and large intestine, and are less common in gastric involvement.

Exon 13 encodes the ATP binding region of the tyrosine kinase domain. Exon 17 encodes the activation loop of the tyrosine kinase domain, its oncogenic mutations lead to higher stability of the activated receptor. These two mutations are more common in small bowel GISTs. It is interesting that usually their histopathological correlate is the spindle cell morphology of the tumor.

Pronounced and diffuse cytoplasmic immunoreactivity for KIT is characteristic of KIT-mutated GISTs, regardless of which part of the gene is affected.

GISTs with a PDGFRA mutation[edit | edit source]

A PDGFRA mutation was described in GISTs without a KIT mutation in 2003. The structure and function of the receptor is similar to the KIT receptor.

The distribution of mutations is not uniform along the entire gene

- mutation in exon 18: 6% of cases

- mutation in exon 12: 1.5% of cases

- mutation in exon 14: 2% of cases

Exon 18 encodes the activation loop of the tyrosine kinase domain. Exon 12 encodes a domain adjacent to the inner side of the cell membrane. Exon 14 encodes the ATP binding region of the tyrosine kinase domain

Accompanying genetic changes[edit | edit source]

In GIS, other characteristic changes in the genetic material often develop. Chromosome 14 is affected in approximately two-thirds of cases, most often monosomy of chromosome 14 and deletion of 14q are demonstrated. Deletion of 22q is demonstrable in about half of the cases. Insertions on 8q, 3q and 17 are common and are associated with more aggressive tumor behavior.

An association with aggressive behavior is also likely with mutations of other genes, especially CDKN2A (cyclin-dependent kinase 2A inhibitor), PI3K PI3K gene , and impairmen cascade.

GIST without KIT and PDGFRA mutation[edit | edit source]

This group accounts for 10-15% of GISTs in adults, but in children they account for up to 90% of all GISTs. Clinically, this is a heterogeneous group of tumors.

GIST s deficitem SDH[edit | edit source]

Succinyl dehydrogenase is actually complex II of the respiratory chain. Loss of A (SDHA) and B (SDHB) subunit activity is a hallmark of GISTs arising as part of the Carney trias (non-hereditary occurrence of gastric GISTs, paragangliomas and pulmonary chondromů) and Carney Stratakis syndrome (hereditary occurrence of gastric GISTs and paragangliomas). Because they are usually (though not exclusively) childhood tumors, SDH-deficient GISTs are sometimes referred to as pediatric GISTs.

They appear more often in women, practically exclusively in the stomach. Unlike other GISTs, metastases to lymph nodes occur here. SDH-deficient GISTs tend to be resistant to imatinib. The development of the disease is gradual, there are described cases of patients who survived for decades with proven metastases in the liver or on the peritoneum

Although characteristic KIT positivity is demonstrated by staining, the gene itself is not mutated. Loss of expression of SDHB and SDHA subunits is demonstrated immunochemically. While loss of SDHA is exclusively associated with gene mutation, loss of SHDB expression is a manifestation of a broader spectrum of disorders involving the entire complex II of the respiratory chain.

The mechanism by which the loss of the succinate dehydrogenase complex leads to the formation of a tumor has not been fully explored. However, that mechanism appears to be succinate accumulation. The increase in succinate induces the stabilization of the transcription factor HIF1-α]], which then leads to the transcription of, among other things, the gene for the cytokine VEGF (Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor).

Accumulation of succinate also inhibits some enzymes dependent on the presence of α-ketoglutarate, especially DNA hydroxylase from the TET family, which, among other things, disrupts the production of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine. As DNA methylation has been shown to be lower in SDH-deficient GISTs than in KIT-mutated GISTs, it appears that an altered DNA methylation pattern may play a role in pathogenesis.

Overexpression of the gene for the receptor for IGF1 (Insulin-like Growth Factor 1) is a relatively common finding in this group of GISTs. The mechanism and meaning are still unclear.

GIST associated with neurofibromatosis type I[edit | edit source]

The pathogenesis of GISTs in patients with neurofibromatosis type I is unknown, although an association is apparent. GISTs most often appear in the small intestine, neither KIT mutation nor PDGFRA mutation can be demonstrated. GISTs often arise on the background of hyperplasia of Cajal cells. An immunochemical peculiarity is that approximately one third of GISTs associated with neurofibromatosis show demonstrable expression of S100 protein. Even in these GISTs, characteristic staining for KIT is visible immunochemically. The behavior of these GISTs is usually biologically favorable.

GIST with BRAF mutation[edit | edit source]

A mutation in exon 15 of the BRAF gene has been identified in approximately 13% of wild-type GISTs. B-Raf is a serine/threonine kinase playing an important role in the RAS-RAF-ERK signaling cascade.

These GISTs occur most often in the small intestine, less often in the stomach. Probably (little data) these are highly malignant tumors that are resistant to imatinib, but show some sensitivity to the BRAF inhibitor dabrafenib.

Obrazová galerie[edit | edit source]

- Makroskopický vzhled

- Microscopic appearance

- Immunochemical staining

Links[edit | edit source]

Virtual preparations[edit | edit source]

- the preparations are part of the documentation of the following article: OTTO, C. – AGAIMY, A. – BRAUN, A.. Multifocal gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) with lymph node metastases in children and young adults: a comparative clinical and histomorphological study of three cases including a new case of Carney triad. Diagn Pathol. [online]. 2011, vol. 6, p. 52, Available from <https://diagnosticpathology.biomedcentral.com/content/6//52>. ISSN 1746-1596.

Related Articles[edit | edit source]

- Riziko progrese a staging GISTů (tabulka, PDF, jedna strana A4)

- Nádory mezenchymové

- Nádory žaludku

Literature[edit | edit source]

- ROSAI, Juan. Ackerman's Surgical Pathology. 8. edition. Mosby, 1996. vol. 1. ISBN 0-8016-7004-7.

- HAMILTON, Stanley R. – AALTONEN, Lauri A.. WHO Classification of Tumours : Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of the Digestive Syste, [online] . 1. edition. IARC Press, 2000. Available from <http://publications.iarc.fr>. ISBN 92-832-2410-8.

- WHO. . Mezinárodní klasifikace nemocí pro onkologii : česká verze. 3. edition. Ústav zdravotnických informací a statistiky, 2004. ISBN 80-7280-373-5.

- LASOTA, J – MIETTINEN, JA. Spindle cell tumor of urinary bladder serosa with phenotypic and genotypic features of gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Arch Path Lab Med [online]. 2000, y. 124, vol. 6, p. 894-897, Available from <http://www.archivesofpathology.org/doi/full/10.1043/0003-9985%282000%29124%3C0894:SCTOUB%3E2.0.CO;2>. ISSN 1543-2165.

- MIETTINEN, M – LASOTA, J. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: Pathology and prognosis at different sites. Sem Diagn Pathol. 2006, y. 23, vol. 2, p. 70-83, ISSN 0740-2570.

- DOW, N – GIBLEN, G. , et al. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: Differential diagnosis. Sem Diagn Pathol. 2006, y. 23, vol. 2, p. 111-119, ISSN 0740-2570.

- KOH, J.S. – TRENT, J – CHEN, L. , et al. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: Overview of pathologic features, molecular biology, and therapy with imatinib mesylate. Histol Histopatol. 2004, y. 19, vol. 2, p. 565-574, ISSN 1699-5848.

- DOYLE, L.A. – HORNICK, J.L.. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: From KIT to succinate dehydrogenase. Histopathology. 2014, y. 64, vol. 1, p. 53-67, ISSN 1365-2559.

- National Cancer Institute (USA). Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors Treatment : Stage Information for Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors [online]. [cit. 4/2014]. <https://www.cancer.gov/types/soft-tissue-sarcoma/hp/gist-treatment-pdq#section/all>.

- DAUM, O. – ŠEDIVCOVÁ, M.. Doporučený postup pro histologické vyšetření gastrointestinálních stromálních tumorů. Společnost českých patologů, 2014.

External links[edit | edit source]

- reGISTer – registr pro sběr epidemiologických a klinických dat pacientů s gastrointestinálním stromálním tumorem

- BEHAZIN, Nancy S.. Medscape [online]. [cit. 2014]. <https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/278845-overview,>.

- CHOTI, Michael. Medscape : Gastric Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumor [online]. ©2013. [cit. 2014]. <https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/278845-overview>.

- PathologyOutlines.com. Stomach > Stromal/other tumors > Gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) [online]. ©2012. [cit. 2014]. <http://www.pathologyoutlines.com/topic/stomachGIST.html>.

- PathologyOutlines.com. Esophagus > Other malignancies > Gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) [online]. ©2012. [cit. 2014]. <http://www.pathologyoutlines.com/topic/esophagusGIST.html>.

- PathologyOutlines.com. Small bowel (small intestine) > Other malignancies >Gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) [online]. ©2012. [cit. 2014]. <http://www.pathologyoutlines.com/topic/smallbowelGIST.html>.

- PathologyOutlines.com. Liver and intrahepatic bile ducts - tumor > Other malignancies > Gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) [online]. ©2012. [cit. 2014]. <http://www.pathologyoutlines.com/topic/livertumorGIST.html>.

- PathologyOutlines.com. Stains > DOG-1 [online]. ©2011. [cit. 2014]. <http://www.pathologyoutlines.com/topic/stainsDOG1.html>.

- ŽABKA, J. Gastrointestinální stromální tumory. Klin Cnkol [online]. 2011, y. 24, vol. 3, p. 187-194, Available from <http://www.eonkologie.cz/klinicka-onkologie/archiv/2011/53-archiv/2011-3/248-2011-03zabka>. ISSN 0862-495X.

- DAUM, O – ŠÍMA, R – MICHAL, M. Patologická diagnostika gastrointestinálního stromálního tumoru. Onkologie [online]. 2010, y. 4, no. 1, p. 13-17, Available from <http://www.onkologiecs.cz/pdfs/xon/2010/01/04.pdf>. ISSN 1803-5345.