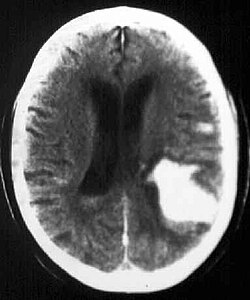

Bleeding into the brain parenchyma

Bleeding into the brain parenchyma (intraparenchymatous hemorrhage, hereafter referred to as IPH) is characterized by a sudden onset focal deficit that worsens within seconds to minutes, often associated with cephalalgia, nausea, vomiting and coma. Aetiology includes hypertension, vascular malformation, vasculopathy, coagulopathy, etc. IPH is reliably demonstrated by CT or MRI. Treatment and prevention of recurrence depend on the aetiology.[1]

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

IPH accounts for approximately 10-15% of strokes with a worldwide incidence of 10-20 cases per 100,000 persons. Incidence is higher in men, in older age, and in black and Asian populations. Other risk factors include hypertension, smoking, alcoholism (-> cirrhosis, thrombocytopenia) or low serum cholesterol (e.g. after intensive statin therapy). Among genetic risk factors, the presence of alleles for apolipoprotein E ε2 and ε4' are implicated in amyloid deposition in cerebral vessels, and amyloid angiopathy.[1]

Pathogenesis[edit | edit source]

A hypertensive patient's hemorrhage occurs at the bifurcation of small penetrating arteries, which are scarred and have degenerated media due to hypertension. Another independent cause of IPH is the presence of pathologically altered, fragile vessels due to cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Other causes include:

- vascular malformations (AV malformations, AV fistulas and cavernous angiomas);[1]

- hemorrhagic diathesis (hemophilia, thrombocytopenia, leukemia, liver disease);[2]

- anticoagulation therapy - long-term warfarinization causes IPH in up to 10% of patients, especially when combined with other risk factors;

- Cerebrovenous occlusion in sagittal sinus thrombosis is a rare diagnosis to keep in mind when the risk of thrombus is increased;

- hyperperfusion syndrome in patients who have undergone carotid revascularization endarterectomy, in which cerebral perfusion suddenly increases and leads to headache, confusion, focal deficits, and even IPH;

- substance abuse - sympathomimetics such as amphetamine, methamphetamine and cocaine;

- tumors that can also bleed, such as in high-grade glioblastoma;[1]

- haemorrhagic transformation of ischaemic stroke, where reperfusion injury to ischaemic tissue is involved in the pathogenesis.[3]

The bleeding itself stops spontaneously shortly after the onset of the ictum, and bleeding that persists for several hours is less common (usually in uncorrected coagulopathies). Extravascular blood (hematoma) contains proteins that are osmotic in the brain and contribute to the formation of edema that causes oppression of its surroundings. It is not clear whether ischemia occurs in the surrounding parenchyma; rather, suppression of brain tissue activity (diaschisis) is considered. This hypothesis is supported by the fact that correction of hypertension after IPH is safe.[1]

Clinical picture[edit | edit source]

Patients with IPH develop a focal neurological deficit such as contralateral hemiparesis, loss of hearing, quadriplegia, etc. (depending on the location of the lesion). The deficit worsens within minutes and is often associated with acute hypertension (Cushing's reflex). Increased intracranial pressure due to a hematoma leads to nausea, vomiting and alteration of consciousness.[1]

It should be noted that the clinical picture fails to distinguish between hemorrhagic and ischemic ictus.[1]

Diagnostics[edit | edit source]

The key to the diagnosis of IPH is [CT of the head, which is usually the method of choice for speed of examination.[1] Hemorrhage appears as a hyperdense focus on CT. [2] An alternative is MRI, which is more sensitive than CT for some aspects of IPH, e.g. for vascular malformations or brain tumours on contrast-enhanced MRI with gadolinium.[1]

Other important investigations include:

- bleeding tests (APTT, PT, platelet function);

- [blood count]];

- liver function tests;

- ECG;

- x-ray s+p;

- urine toxicology in selected patients.[1]

In patients younger than 50 years of age with an unexplained source of bleeding, angiography should be performed to exclude vascular anomalies or, in the case of infarction in the venous plexus, venography to exclude venous thrombosis.[1]

Therapeutic approach[edit | edit source]

The goals of treatment are to minimize brain damage and prevent systemic complications:

First contact[edit | edit source]

Provide first aid according to ABC (Airway, Breath, Circulation) rules, intubation in patients with impaired consciousness, bulbar dysfunction or respiratory insufficiency. Look for signs of trauma. If we find an unconscious patient, we treat him as if he had a spinal injury until proven otherwise. Once in bed, the head of the bed should be at a 30° inclination for optimal pressure and perfusion of the brain. If rehydration is necessary, use saline (avoid hypotonic solutions and ringer lactate!). The patient should be admitted urgently to the intensive care unit.[1]

Hemorrhage arrest[edit | edit source]

In 40% of patients, hematoma expansion occurs within 24 hours and is the most common cause of neurological deterioration. The goal is to reduce blood pressure to below 160/90 mmHg. I.v. labetalol or nicardipine is administered. In a hypertensive crisis, sodium nitroprusside is to be considered, but its vasodilating action increases intracranial pressure.[1]

In warfarin-induced IPH, efforts are made to correct the artifactual coagulopathy. In practice, activated factor VII or prothrombin complex concentrate is used.[1]

Surgical management of hematoma evacuation is only used in patients with cerebellar hemorrhage where there is a risk of trunk compression, in patients with vascular malformations (and a good prognosis), and in young patients with moderate to large hemorrhage who are clinically deteriorating. In contrast, surgical management is contraindicated in small bleeding with minor neurological deficits and in patients with GCS below 5, except in those cases of cerebellar hemorrhage mentioned above.[1]

Prevention of the secondary damage[edit | edit source]

The hematoma and subsequent edema increase intracranial pressure (ICP) and contribute to the oppression of surrounding structures, hernia and worsening clinical picture. An ICP-monitor or similarly CT imaging twice daily during the first 48 hours may be used to monitor intracranial pressure to monitor hematoma progression. Anti-hematoma therapy should be used only in the event of neurological clinical deterioration or when a herniation is demonstrated on CT and not prophylactically. Administer Mannitol 0.25-1.0 g/kg in boluses to a target plasma osmolality of 320 mOsm/l. Both mannitol and hyperventilation should be phased out, otherwise, a rebound phenomenon will occur and ICP will rise.[1]

During acute IPH, seizures may occur, which may exacerbate ICP -> anticonvulsants. Corticosteroids are of no value in acute IPH.[1]

Relapse prevention[edit | edit source]

Combination of thiazide diuretics and ACE inhibitors in the control of hypertension reduced recurrence rates by half. Patients with amyloid angiopathy should avoid antiplatelet therapy including aspirin.[1]

Systemic complications[edit | edit source]

These are the same as in all unstable, immobile patients. Complications:

- cardiovascular: IPH is often accompanied by ECG changes and subendocardial ischemia. Antiplatelet therapy should be discontinued for several weeks to prevent coronary ischemia;

- Pulmonary: represents the aspiration of gastric contents and pulmonary embolism in the immobilized. Compression stockings are used in the prevention of embolism, and low-dose heparin or heparinoids are used three days after bleeding in stable patients;

- infectious: pulmonary, urinary, skin, venous;

- metabolic: hyponatremia due to SIADH, isotonic crystalloid therapy;

- mechanical: prevention of decubitus in immobilized patients.[1]

Rehabilitation after a hemorrhagic stroke should, as with ischemic stroke, begin as soon as possible.[2]

Links[edit | edit source]

Related articles[edit | edit source]

External linkls[edit | edit source]

Literature[edit | edit source]

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s BRUST, John C. M. Current diagnosis and treatment, Neurology. 2. edition. Singapore : McGraw-Hill, 2012. ISBN 9780071326957.

- ↑ a b c BEDNAŘÍK, Josef – AMBLER, Zdeněk, et al. Klinická neurologie. Část speciální II. 1. edition. Praha : Triton, 2010. ISBN 9788073873899.

- ↑ LIEBESKIND, Davis S. Hemorrhagic stroke [online]. The last revision 8.3.2013, [cit. 2013-03-22]. <https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1916662-overview>.