Hypothyroidism

Hypothyroidism is a reduced thyroid function with insufficient secretion of thyroid hormones.

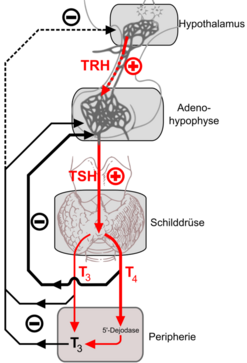

According to the cause of hormone deficiency, we divide hypothyroidism into:

- primary (peripheral) – cause in the thyroid gland (lack of peripheral thyroid hormones);

- secondary (central) – cause in the pituitary gland (TSH deficiency);

- tertiary (central) – cause in the Hypotalamuss (lack of TRH)

Peripheral hypothyroidism[edit | edit source]

Causes:

- chronic autoimmunne thyroiditis (idiopathic myxedema);

- thyroid aplasia or ectopia;

- gland destruction (after thyroidectomy, throat irradiation, after radioiodine treatment);

- with severe iodine deficiency in the diet (endemic cretinism);

- after thyreostatics;

- congenital disorders:

- iodide transport defect (gen for NIS – sodium-iodide symporter)

- TSH resistance (TSHR membrane receptor gene);

- thyreoglobulin defect (thyreoglobulin substrate gene);

- pseudohypoparathyroidism type la (gene for transducer GNAS1 – guanine nucleotide-binding protein, α-stimulating polypeptide) – AD disease, also includes resistance to TSH;

- thyroid hormone resistance (TRβ nuclear receptor gene) – hormone levels may be elevated

- due to drugs (lithium, PAD, amiodarone) and strumigens.

Clinical manifestation[edit | edit source]

- fatigue, drowsiness, shivers, a tendency to depression, bradyphrenia;

- dry skin on the forearm – Charvat's symptom, myxedema – swelling of the lower leg, face with hypomimia, subsequent involvement of the tongue and vocal cords, which causes a deep voice;

- overweight (but not obesity);

- constipation;

- myxedemic cardiomyopathy (bradycardia, pericardial affusion, arrhythmia), accentuation of atherosclerosis;

- anemia;

- impotence in men, sterility in women, menstrual disorders;

- in the elderly, the symptoms are often discrete or absent (oligosymptomatic form).

Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

- In the laboratory, there are lower values of T3 and T4 and higher TSH, or a test with i.v. application of TRH is performed to distinguish the peripheral form from the central one;

- In autoimmune hypothyroidism, the presence of antibodies (against TSH-receptors, thyroglobulin, thyroid peroxidase) is demonstrated;

- Ultrasound examination, which shows a possible change in gland tissue (occurrence of nodules);

- Cholesterol and TAG, higher CK, LDH and aminotransferases may be elevated in a laboratory.

- In some cases, anemia can occur.

- Subclinical hypothyroidism

- TSH elevation ;

- T3 and T4 are normal (practically almost exclusively free thyroxine is measured – fT4, which is biologically active);

- often without clinical symptoms, hormone replacement therapy just in case of clinical symptoms;

- it usually turns into a manifest form later.

Treatment[edit | edit source]

Levothyroxin (Euthyrox®, maintenance dose 100–150 μg/day or Letrox®), a T4 analogue, is substituted. Synthetic T3 analogues are given just in case of insufficient response to levothyroxine treatment. The control of treatment is important – the level of TSH is determined as a parameter to compensate for hypothyroidism. In severe hypothyroidism, minimal doses of levothyroxine are initially given and gradually increased very slowly (otherwise there is a risk of thyrotoxicosis).

Central hypothyroidism[edit | edit source]

Causes:

- congenital:

- isolated TSH deficiency (TSHβ gene),

- PIT1 abnormalities (PIT1 transcription factor gene),

- PROP1 defect (gene for transcription factor PROP1),

- TRHR defect (TRHR membrane receptor gene),

- TSH deficiency (isolated, panhypopituitarism) or TRH for various reasons:

- pituitary or hypothalamic involvement in an expansion process;

- CNS inflammations and trauma;

- pituitary bleeding, postpartum pituitary necrosis (Sheehan's syndrome).

It's mostly hypothyroidism that originated as a part of hypopituitarism, dominated by symptoms of hypocorticism, the treatment of which also takes precedence over the correction of hypothyroidism. It manifests itself mainly in fatigue and drowsiness, lacking myxedema and usually goitre, TSH is not increased (usually its level is normal), the main feature is a decrease in fT4 and other signs of hypopituitarism, it's necessary to examine the hypothalamic-pituitary region by imaging methods (CT, NMR). Treatment is also substitutive (Levothyroxine). It is used only after thy hypocortisolism has been compensated by glucocorticoids.

Complications[edit | edit source]

Myxedema coma is the escalation of symptoms of hypothyroidism into a life-threatening condition. The body temperature decreases, the affected person hypoventilates with hypercapnia, so drowsiness manifests itself, which can turn into a comatose state. The victim is also at risk of bradycardia, arrhythmias and heart failure. The cause of these conditions is untreated or poorly treated hypothyroidism when the body is exposed to stress (cold, infection, injury, surgery,...). The diagnosis does not differ from the procedure in peripheral hypothyroidism. Treatment consists of circulatory and respiration (intubation with artificial lung ventilation) control, serving Levothyroxine, glucocorticoids (current adrenal insufficiency cannot be ruled out), preventive ATB and gradual warming.

Euthyroid sick syndrome (ESS)[edit | edit source]

ESS is a syndrome characterized by changes in thyroid hormones in the clinical manifestation of euthyroidism, which accompanies diseases of other systems. It occurs in acute and chronic diseases, injuries, after surgeries, conditions of malnutrition, starvation and premature infants. In the laboratory, we find decreased fT3, normal or decreased fT4 and normal TSH. ESS is thought to be an adaptive response in the body to minimize catabolism and O2 consumption during stress. After the basic disease has improved, thyroid hormones return to normal. ESS therapy focuses on the basic disease.

References[edit | edit source]

Related articles[edit | edit source]

- Thyroid gland

- Hyperthyroidism

- Examination for thyroid diseases

- Examination of thyroid function

- Symptomatic mental disorders in endocrinopathies

External links[edit | edit source]

Source[edit | edit source]

- PASTOR, Jan. Langenbeck's medical web page [online]. ©2006. [cit. 26.10.2010]. <https://langenbeck.webs.com/interna.htm>.

Literature[edit | edit source]

- MASOPUST, Jaroslav – PRŮŠA, Richard. Patobiochemie metabolických drah. 2. edition. Univerzita Karlova, 2004. 208 pp.